Quick summary! In August 2018 I was forced by the unhinged intransigence of Blair Besten, half-pint Norma Desmond of the Historic Core BID, to file a petition seeking to enforce my rights under the California Public Records Act. So the usual on-and-freaking-on process of CPRA litigation happened and after a few archetypally zany moments, like La Besten denying under oath that those things her BID sends out via MailChimp are, you know, emails, everybody filed their briefs in July and on November 5, 2019 we finally had the damn trial and the BID lost big freaking time!

And when a local agency such as a BID loses a CPRA case the law is very clear. The judge must award costs and fees to the requester.1 It doesn’t happen automatically, though. The prevailing requester has to file a fee motion and if the parties can’t agree on it there’s a hearing. So we filed the motion, and by “we” I mean my attorney, the incomparable Colleen Flynn, and here’s a copy of the fee motion. The BID flipped out and you can read their reply to the fee motion and our reply to their reply if reading a flipout is interesting to you.

We were supposed to have a hearing in May, but of course that didn’t happen. However, the judge did issue a tentative ruling, of which there is a transcription below, and awarded us $39,720 in fees and $1,099.25 in costs. This may seem high, but Chalfant cut Flynn’s hourly rate from $740 to $400 based on his unarticulated evaluation of the difficulty of the case and the level of expertise involved, which apparently judges mostly just have the discretion to do.

The BID’s theory, as usual, is that I’m only filing CPRA requests to trick them into violating the law so I can sue them, make them pay a lot of money, and eventually drive BIDs out of business. This, of course, is stupid. If they didn’t violate the law they wouldn’t have to pay anything. If they handed over the records and then settled like normal people they’d almost surely have to pay under $10K.

But the Historic Core BID chose not to do an adequate search for the records, chose not to produce them after I asked repeatedly for way over a year, and chose to fight the case all the way to the bitter end. The fact that they have to pay $40K is entirely their own fault and it’s ridiculous of them to whine about it, especially with such an implausible story.

The story may be implausible but the tentative ruling suggests that Chalfant buys in to it. He says that “[t]he court sympathizes with HCBID’s concern that [Kohlhaas] – who is a serial CPRA requester from BIDs – is abusing the CPRA system.” It ultimately doesn’t matter, though. The CPRA explicitly states that the requester’s purpose is irrelevant2 and Chalfant recognizes this fact and states it in his ruling.

It’s a little disconcerting by the way that he encourages the BID to take legal action against me for my purported abuse of the CPRA. In particular, he says that “HCBID, and other BIDs have other remedies against [Kohlhaas], including declaratory and injunctive relief against his abuse.” Probably he’s just shooting off his big fat judicial mouth about this, but who knows? Anyway, that’s the end of that story! Now stay tuned for more records and more mockery of the Historic Core BID and all the fash weirdos that run it.3

Transcription of Judge Chalfant’s tentative ruling in this case:4

[M. Kohlhaas] v. Historic Core Business Improvement District, BS174718

Tentative decision on motion for attorney fees: granted in part

Petitioner [Michael Kohlhaas] (“[Kohlhaas]”) moves for an award of attorney’s fees against Respondent Historic Core Business Improvement District Property Owners Association (“HCBID”) in the amount of $77,182.

The court has read and considered the moving papers, opposition, 1 and reply, and renders the following tentative decision.

A. Statement of the Case

1. Petition

On August 13, 2018, [Kohlhaas] filed the Petition for writ of mandate, which alleges in pertinent part as follows.

[Kohlhaas] is a resident of Los Angeles who publishes a blog where he regularly reports on information obtained through CPRA requests.HCBID is a property owners’ association created by the City of Los Angeles (“City”) pursuant to the Property and Business Improvement District Law of 1994, Streets & Highways Code §§36600 et seq., that manages the Historic Core’s Business Improvement District (“BID”). HCBID is subject to the CPRA.

[Kohlhaas] made five CPRA requests on many different dates to discover how HCBID’s staff and board of directors influence local officials and legislation, especially involving HCBID’s renewal process for its BID. Id. §Overview, ¶¶ 2-3. Generally, [Kohlhaas] alleges that HCBID engaged in a pattern of non-compliance, delay, obstruction, and broken promises of compliance amounting to a wrongful refusal to produce requested records under the CPRA. [Kohlhaas] seeks (1) a writ of mandate directing HCBID to immediately conduct a diligent and comprehensive search for the requested records and promptly produce those records, (2) a declaration that HCBID has violated CPRA, (3) an order for HCBID to produce all responsive records to any future requests within 30 days unless HCBID shows an extraordinary hardship, and (4) reasonable attorney fees and costs.2. Course of Proceedings

On November 5, 2019, the court granted in part [Kohlhaas]’s petition for writ of mandate. The court directed HCBID to conduct a new search for the January 27, 2017 request to ensure that no electronic records were missing; HCBID should produce the 11 printed emails in native electronic format or else explain why they cannot be found. HCBID should also conduct a new search and produce mailchimp emails responsive to [Kohlhaas]’s CPRA requests other than the first request.

B. Applicable Law

Government Code section 6259(d) provides in part: “The court shall award court costs and reasonable attorney fees to the plaintiff should the plaintiff prevail in litigation filed pursuant to this section. The costs and fees shall be paid by the public agency of which the public official is a member or employee and shall not become a personal liability of the public official.” An award of attorney fees pursuant to this subdivision is mandatory if the plaintiff prevails.

The attorney’s fees provision of the CPRA should be interpreted in light of the overall remedial purpose of the CPRA to broaden access to public records. To this end, the purpose of the attorney’s fees provision is to provide protections and incentives for members of the public to seek judicial enforcement of the right to inspect public records subject to disclosure.

C. Statement of Facts

1. Petitioner’s Evidence

On February 10, 2020, Respondent’s attorney Jeff Briggs, Esq. (“Briggs”) emailed [Kohlhaas]’s attorney, Colleen Flynn, Esq. (“Flynn”) the mailchimp files which the court had ordered disclosed. ¶2. Flynn forwarded the files to [Kohlhaas].

On December 23, 2019, Flynn emailed Briggs with an offer to resolve fees and costs, inviting a counter-offer. She sent a follow-up email on February 10, 2020 before beginning work on the instant motion. Flynn did not receive a substantive response to the offer of settlement.

[Kohlhaas] has incurred costs in the instant matter of $541.25 (filing fees), $522.00 (transcript for the Blair Besten (“Besten”) deposition), $35 (messenger services), and $1 (postage). The total costs are $1099.25.Flynn has experience in FOIA/CPRA cases and has previously represented [Kohlhaas] in another CPRA case in 2018, for which she was awarded $30,000 in attorney fees.

Flynn maintained contemporaneous time records using Excel, which reflect that she spent 99.3 hours on the instant matter. Flynn requests an hourly rate of $740 for her time spent on the instant matter and bases this amount on the opinions of attorneys Carol A. Sobel (“Sobel”) and Richard M. Pearl (“Pearl”), who are experts in issues related to court-awarded attorney feels and are familiar with hourly rates awarded to attorneys with similar experience.

Sobel and Pearl both opine that Flynn’s requested rate is reasonable, based on their experience with and understanding of the market rates billed by attorneys with equivalent experience in similar litigation in the Los Angeles area.

Flynn also bases her request on fee awards to other attorneys of similar skill and experience. In 2018, Flynn received fees at a rate of $600 per hour for representing [Kohlhaas] in another CPRA matter. In 2016, she was awarded fees at a rate of $590 per hour for a FOIA case.

2. Respondent’s Evidence

Briggs represents or has represented approximately 14 other BIDs responding/opposing [Kohlhaas]’s many CPRA requests since 2014.

Briggs began assisting Respondent in connection with [Kohlhaas]’s CPRA request after HCBID responded to the January 27, 2017 request, the first of five requests at issue.

Respondent was attending to [Kohlhaas]’s other four requests, the responses to which were concluded in May 2018. While expressing frustration with the delays in Respondent’s responses, at no time prior to the filing of the Petition in August 2018 did [Kohlhaas] question the substance of Respondent’s responses to any of the five requests.

During Briggs’ assistance of other BIDs for [Kohlhaas]’s CPRA requests, [Kohlhaas] often expressed frustration over the time it took for the BIDs to respond, resulting in agreements by two BIDs represented by Briggs to provide responsive records on an amended timeframe.

This amended timeframe was the same as that stipulated to by [Kohlhaas] in this case; Respondent would have agreed to that amended timeframe had [Kohlhaas] asked for it before filing suit.

At Respondent’s deposition, [Kohlhaas] for the first time raised a question about whether Respondent had searched for “emails” sent by a vendor, Streetplus, using a Respondent email address, and emails sent by its third-party announcement and newsletter vendor, mailchimp. Respondent explained that the minimal use of its email by Streetplus had been overlooked, and the few additional records promptly were provided.

Briggs offered to discuss the mailchimp issue in exchange for equal consideration of [Kohlhaas]’s use of Respondent’s old domain name to re-direct HCBID traffic to his own website critical of HCBID, and Petitioner’s use of a Respondent staffer’s photo as his own Twitter identifier. Briggs never received any response.

Virtually every [Kohlhaas] request to various BIDs has included a request for emails. [Kohlhaas]’s requests are often specific in terms of the electronic format in which he seeks responsive productions, specifically requiring the “meta data” embedded in the electronic versions of records. Despite [Kohlhaas]’s demonstrated knowledge of email systems, he never asked any of the BIDs, including Respondent, for mailchimp “emails” whether in an original written CPRA request or any follow-up inquiry as to the completeness of a response. The mailchimp email issue has not arisen in any of the other three CPRA request litigations in which [Kohlhaas] and Briggs have been involved.

Briggs emailed [Kohlhaas]’s counsel to provide the mailchimp records and explain why no additional records were found in response to the first of [Kohlhaas]’s requests. The email contains links to Respondent’s announcements sent by mailchimp, and true copies of a sample of such an announcement, and of one of the several spreadsheets sent with lists of mailchimp recipients. [Kohlhaas] never challenged this response.

[Kohlhaas]’s offer to settle the instant motion was made well before Respondent had completed its obligations under the writ, which ultimately resulted in no additional records being produced except the mailchimp records. [Kohlhaas]’s counsel made it clear that the minimal offer Respondent might be willing to make would not be acceptable.Briggs’ usual rate for commercial litigation is $500 per hour but he charges Respondent and other public interest and non-profit entities a lower rate of $250 per hour.

D. Analysis

[Kohlhaas] seeks a total attorneys’ fees award of $77,182 plus $1,099.25 in costs. HCBID opposes.1. Entitlement to Fees

An award of attorney fees pursuant to section 6259(d) is mandatory if the plaintiff prevails. For purposes of section 6259(d), a “prevailing party” is one who “succeeds on any significant issue in the litigation and achieves some of the benefit sought in the lawsuit.” A plaintiff prevails under the CPRA if the action simply results in the release of previously withheld documents, for purposes of attorney fees and costs provision of the Act, if the lawsuit motivated the defendants to produce the documents.

HCBID argues that [Kohlhaas] is not entitled to an award of attorney fees because he is not a prevailing party under the CPRA. HCBID asserts that [Kohlhaas] is not a prevailing party because the litigation did not result in the production of any additional records and because [Kohlhaas] cannot demonstrate that the litigation was necessary. HCBID notes that the only relief ordered by the court was that HCBID to conduct an additional search to ensure that no electronic records were missing from the hard copies already produced and to produce the mailchimp emails.

HCBID asserts that the only new documents produced were the mailchimp “emails”, which are not real emails and rather are a list of recipients of an announcement and the announcement itself and a few additional emails to and from one of HCBID’s vendors, Streetplus, which were promptly provided when asked. The mailchimp documents were not contemplated in [Kohlhaas]’s initial request or asked for before the litigation commenced.

HCBID argues that [Kohlhaas] did not give it a chance to comply with these minor issues prior to filing suit. As a result, litigation was not necessary, or the motivating factor for, HCBID’s production of any of the produced documents.

The court’s November 5, 2019 decision in this case noted that HCBID acted in good faith and made serious compliance efforts. Nonetheless, [Kohlhaas]’s lawsuit was the catalyst for production. HCBID admits that it only produced the mailchimp documents due to the court’s order, and [Kohlhaas] correctly notes that the court found HCBID’s argument that mailchimp documents are not emails to be disingenuous in its November 5 decision.

[Kohlhaas] may not specifically have asked for mailchimp files in his initial request or at any point after initial production, but he correctly notes that HCBID has the burden to know what responsive records it has and to produce them.HCBID produced the mailchimp emails as a direct result of a court order. Similarly, the Streetplus emails were produced four months after the lawsuit was filed and only on December 31, 2018 as a result of the parties’ meet and confer ordered by the court. Finally, HCBID produced unredacted electronic records after the same meet and confer.

[Kohlhaas] is the prevailing party because the lawsuit resulted in the production of these previously unproduced documents.3. Reasonableness of Fees

The court employs the lodestar method when looking to determine the reasonableness of an attorney’s fee award. The lodestar figure is calculated by multiplying the number of hours reasonably spent by the reasonable market billing rate.

4a. Reasonable Rates

Generally, the reasonable hourly rate used for the lodestar calculation is the rate prevailing in the community for similar work. In making its calculation, the court may rely on its own knowledge and familiarity with the legal market, as well as the experience, skill, and reputation of the attorney requesting fees, the difficulty or complexity of the litigation to which that skill was applied, and affidavits from other attorneys regarding prevailing fees in the community and rate determinations in other cases.

[Kohlhaas] requests a rate of $740 for Attorney Flynn. [Kohlhaas] asserts that this rate is reasonable for lawyers with these levels of experience, and are consistent with rates charged by, and awarded to, other comparably skilled attorneys in the Los Angeles area. In support of its assertion that the requested rate is within the range charged by Los Angeles law firms and are therefore presumptively reasonable, [Kohlhaas] relies on declarations from Sobel and Pearl and other FOIA/CPRA cases that found similar rates to be reasonable.The court agrees with HCBID that the requested rate is unreasonable. The $740 per hour rate is inconsistent with the rates prevailing in the community for this type of work, as well as the relatively simple nature of this lawsuit. The court is not required to rely on Flynn’s level of experience, the range of rates charged by Los Angeles law firms, or the declarations of Sobel and Pearl claiming that the requested rates are approximately in the same range or less than the rates charged by similar firms.

HCBID’s counsel, Briggs, charged an hourly rate of $250 despite having many more years of experience than Flynn. While this is a pertinent factor, [Kohlhaas] correctly notes that the rate of opposing counsel does not control because defense counsel has ongoing business from clients and can work for discounted rates.

The fact is that CPRA claims are generally not complex, and CPRA claims to BIDs are particularly simple because a BID has a limited business and a limited number of records. As HCBID points out, [Kohlhaas] principally seeks emails from BIDs in his CPRA requests and the litigation to compel this production is straightforward. Having in mind Briggs’ $250 hourly rate, the court exercises its discretion to reduce Flynn’s rate to $400 per hour.

b. Reasonable Number of Hours

An attorney’s fee award should ordinarily include compensation only for all the hours reasonably spent on the litigation. The trial court must carefully review attorney documentation of hours expended and eliminate padding in the form of inefficient or duplicative efforts.

[Kohlhaas] provides Flynn’s contemporaneous time billing entries in support of the claimed 99.3 4 hours spent on the instant matter. HCBID does not dispute Flynn’s hours as properly incurred.5c. Apportionment

Although Flynn actually incurred the hours stated, HCBID argues that the fees should be apportioned. The premise of [Kohlhaas]’s Petition was that HCBID failed to adequately search in response to five separate CPRA requests. The court’s decision rejected this premise except one additional search which resulted in no additional electronic records and the production of mailchimp emails which are not emails at all.

The court should award [Kohlhaas] a small fraction of his fees, particularly in light of the fact that [Kohlhaas] makes no pretense that his goal is to drive BIDs out of business through his CPRA requests.

HCBID’s argument ignores the catalyst nature of the lawsuit in compelling further action. The court sympathizes with HCBID’s concern that [Kohlhaas] – who is a serial CPRA requester from BIDs – is abusing the CPRA system. A public agency has a duty to disclose public records under the CPRA, but the disclosure of public records is not the reason for the public agency’s existence. However, a requester’s motive is not relevant to whether he/she is entitled to records under the CPRA, and neither is that motive relevant to the award of attorney’s fees. HCBID, and other BIDs have other remedies against [Kohlhaas], including declaratory and injunctive relief against his abuse.

[Kohlhaas] is entitled to an attorney’s fee award without apportionment.E. Conclusion

[Kohlhaas]’s motion for attorney’s fees is granted in the sum of $39,720, plus costs of$1,099.25.

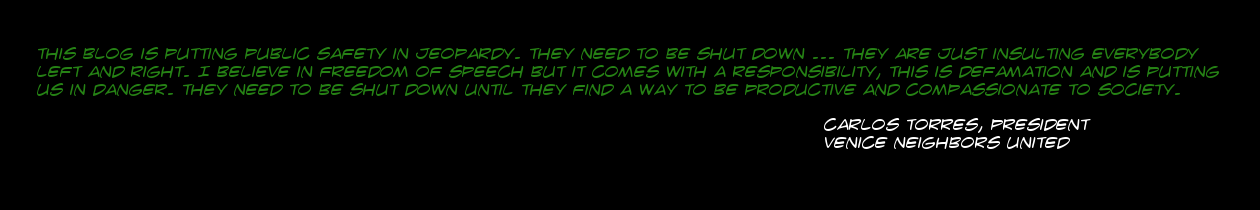

Image of Hollywood Superlawyer Jeffrey Charles Briggs is © 2020 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and if you wanna look the look you gotta click the click!

- Hanging around lawyers has made the distinction between costs and fees seem natural to me, but I remember that at some point it didn’t actually make any sense to me whatsoever. Costs are amounts that a party had to pay out of pocket to carry on the case. Like filing fees, paying court reporters, expert witnesses, and so on. Fees are amounts earned by lawyers for their work but that don’t necessarily correspond to any actual payments. The CPRA specifies that both must be awarded to a prevailing petitioner. This is found in the CPRA at §6259(d), which says: “The court shall award court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees to the requester should the requester prevail in litigation filed pursuant to this section.”

- This is at §6257.5, which says in its entirety: “This chapter does not allow limitations on access to a public record based upon the purpose for which the record is being requested, if the record is otherwise subject to disclosure.”

- Yes, I have already started requesting records from the HCBID again! Blair Besten, the maniacal half-pint Norma Desmond of Fifth Street, has been too long absent from these pages! Not much longer!!

- I cleaned this up a little by omitting footnotes and citations and stuff. If you need any of that info it’s all in the original PDF.