You may recall that Assemblymember Miguel Santiago, a through-and-through creature of the BIDs of Downtown Los Angeles, has been pushing a bill, AB-1971, to redefine grave disability in California in order to allow cities to lock up homeless people on even more superficial pretexts than are currently available to them.

You may recall that Assemblymember Miguel Santiago, a through-and-through creature of the BIDs of Downtown Los Angeles, has been pushing a bill, AB-1971, to redefine grave disability in California in order to allow cities to lock up homeless people on even more superficial pretexts than are currently available to them.

The prospect of this, of course, has BIDs all over the City messing their jeans in joy, and therefore has our esteemed councilbabies messing theirs at the thought of the copious contributions soon to swell their officeholder accounts.1 So much did this unconstitutional jive mean to our Council that they memorialized their support in Council File 18-0002-S11 and also went about the place giving dog-whistle-filled speeches to their BIDdie constituencies.

But despite Santiago and the BIDs and the LA City Council dressing the proposal up as somehow related to compassion or other human emotions, it was pretty clear to everyone that it was nothing more than another tool to facilitate the detention and removal of homeless human beings from our streets. Thus did opposition begin to build, even to the point where, last week, the Los Angeles Times Editorial Board, in no way known for its leftie firebrandism, came out against the bill for precisely the right reasons:

… it’s odd that so much attention is devoted instead to making it easier for authorities to force mentally ill homeless people into involuntary treatment even if they are not an immediate danger to themselves or to others. Once we grab them — and remove them from whatever comfort or support structure they have managed to create — where do we put them? If we force them into hospitals for medical treatment they say they don’t want, then what?

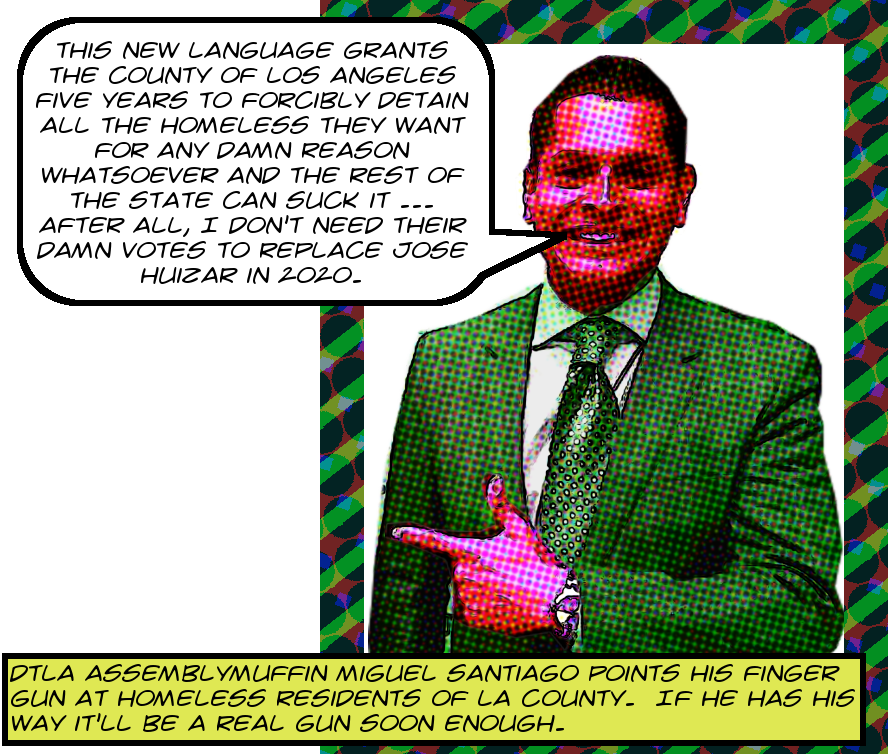

Well, evidently the opposition grew strong enough that yesterday Miguel Santiago felt forced to amend his cynical creation. Amazingly, though, he didn’t change its substance, but only its scope. The new version, if adopted, would expire on January 1, 2024 and, most bizarrely, would apply only in Los Angeles County. Turn the page for some more commentary and a red-lined summary version of yesterday’s changes.

Regardless of how one feels about redefining grave disability, it ought to be clear to anyone who believes in the rule of law that the state shouldn’t have the ability to limit one’s constitutional rights based solely on which county one lives in. If a person ought to be locked up against their will it surely shouldn’t matter which side of some imaginary line they happen to be on.

And the sunset provision is as ridiculous. If these changes are the right changes to make, if they’re necessary, if they alter the definition of grave disability in California to what it ought to be, then why have them expire in five years? It looks as if Miguel Santiago has given up on any pretense of compassion, or of doing right, and instead is telling the City of Los Angeles and its BIDs that it has five years to use this draconian tool to clear the street of homeless residents.

But evidently at this point Miguel Santiago, who desperately wants to inherit José Huizar’s CD14 seat, is so intent on pleasing local business improvement districts that he can’t any longer concentrate on such constitutional niceties. If you ask me, this suggests that the whole bill is headed for failure, although no one ever went broke underestimating the sheer cynicism of a bunch of politicians, who may well jump at this chance to do a favor for a colleague as long as it doesn’t apply in their districts. Stay tuned for further developments.

LEGISLATIVE COUNSEL’S DIGEST

AB 1971, as amended, Santiago. Mental health services: involuntary detention: gravely disabled.

Existing law, the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, authorizes the involuntary commitment and treatment of persons with specified mental health disorders for the protection of the persons so committed. Under the act, if a person, as a result of a mental health disorder, is a danger to others, or to himself or herself, or is gravely disabled, he or she may, upon probable cause, be taken into custody by a peace officer, a member of the attending staff of an evaluation facility, designated members of a mobile crisis team, or another designated professional person, and placed in a facility designated by the county and approved by the State Department of Social Services as a facility for 72-hour treatment and evaluation. For these purposes, existing law defines “gravely disabled” to mean either a condition in which a person, as a result of a mental health disorder or chronic alcoholism, is unable to provide for his or her basic personal needs for food, clothing, or shelter, or a condition in which a person has been found mentally incompetent, as specified. Existing law also provides immunity from civil and criminal liability for the detention by specified licensed general acute care hospitals, licensed acute psychiatric hospitals, licensed professional staff at those hospitals, or any physician and surgeon providing emergency medical services in any department of those hospitals if various conditions are met, including that the detained person cannot be safely released from the hospital because, in the opinion of treating staff, the person, as a result of a mental health disorder, presents a danger to himself or herself, or others, or is gravely disabled, as defined.

This bill would expand the definition of “gravely disabled” for these purposes to also include a condition in which a person, as a result of a mental health disorder or chronic alcoholism, as applicable, is unable to provide for his or her medical treatment, as specified. The bill would make conforming changes. The bill would make certain legislative findings and declarations related to mental health.

Existing law prohibits a person from being tried or adjudged to punishment while that person is mentally incompetent. Existing law establishes a process by which a defendant’s mental competency is evaluated and by which the defendant is committed to a facility for treatment. If the defendant is gravely disabled, as defined above, upon his or her return to the committing court, existing law requires the court to order the conservatorship investigator of the county to initiate conservatorship proceedings on the basis that the indictment or information pending against the person charges a felony involving death, great bodily harm, or a serious threat to the physical well-being of another person.

This bill would, until January 1, 2024, expand the definition of “gravely disabled” for these purposes, as implemented in the County of Los Angeles, to also include a condition in which a person, as a result of a mental health disorder, is unable to provide for his or her basic personal needs for medical treatment, if the failure to receive medical treatment, as defined, results in a deteriorating physical condition that a medical professional, in his or her best medical judgment, attests in writing, will more likely than not, lead to death within 6 months, as specified.

The bill would, on or before January 1, 2023, require the County of Los Angeles to submit a report to the Legislature evaluating the impact of the county’s implementation of the above-mentioned provisions of the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act between January 1, 2019, and June 30, 2022, inclusive, with the expanded definition of “gravely disabled.” The bill would also make certain legislative findings and declarations related to mental health.

By expanding the above definition of “gravely disabled,” “gravely disabled” in, and imposing new duties on, the County of Los Angeles, the bill would increase the duties on local agencies, and would therefore impose a state-mandated local program.

This bill would make legislative findings and declarations as to the necessity of a special statute for the County of Los Angeles.

The California Constitution requires the state to reimburse local agencies and school districts for certain costs mandated by the state. Statutory provisions establish procedures for making that reimbursement.

This bill would provide that, if the Commission on State Mandates determines that the bill contains costs mandated by the state, reimbursement for those costs shall be made pursuant to the statutory provisions noted above.

Image of Miguel Santiago, José Huizar’s hand-picked successor to the CD14 throne, is ©2018 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and is moofled up outta this little Miguel Santiago right here.