I’ll move on to the serious matters below, but first, check this description of protagonists Elwin Carter and Sable having an evening out in 1973:

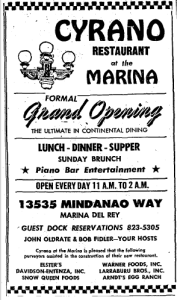

Now, I don’t just read novels for Los Angeles geography porn, but I’m always happy to find it, especially when it has restaurants! Cyrano was a “fine dining” or “continental” sort of place, opened early on in Marina Del Rey. Given the character of the Marina in 1973, at the time Elwin and Sable had dinner there the joint was probably full of cocaine, swinging-in-the-worst-sense, disgusting 1970s facial hair, and gelatinous sleaze coating every surface.

The Name of the Game was a dance place in Inglewood at Century and Crenshaw. Here’s how the Los Angeles Sentinel described it on September 2, 1971:

It’s called The Name of The Game, and to many, many persons it’s the name of the place they find attractive and a lively cynosure for a truly good evening of pleasure. Located at 3000 W. Century boulevard, it has music by Dave Holden, and dancing space for frisky feet or those who just love to move and groove. There’s no cover charge, either. The Name of the Game also affords daily luncheon specials, and daily half-price cocktails. So what could be better for the jaded tastes than a visit to The Name of the Game?4

Unfortunately I can’t find a picture of the place. Note also that there was a sensational killing there in 1973. I don’t have space to go into it, but it was well covered in the Sentinel, starting here.11

Next they head off to the Lighthouse, a famous and still-active jazz club in Hermosa Beach which I’d discuss more if I gave even a fraction of a shit about either jazz or Hermosa Beach. Finally, “on the way home,” they head to Shelley’s Manne Hole which, coincidentally, played an important role in my last recommendation, so I won’t belabor it here. However, these two live in Baldwin Hills, meaning that the Manne Hole, at 1608 N. Cahuenga Blvd., is in no sense but the sense that this night should never end on the way home from Hermosa Beach. Ah, youth!

Now, despite my breathless temporogeographical musings, this novel is much more than a travelogue. It’s an immensely important document about the state of racial politics in Los Angeles eight years after the Watts Rebellion, with more than a little relevance for the present day (as well as being a bitchin’ thriller). Read on for details!

Before we even get to the plot of the novel (which I’m not going to discuss in detail since God hates a spoiler), I want to talk about a few of Jefferson’s asides on segregated housing in Los Angeles at the time. First, e.g., he says of Baldwin Hills:

This is interesting because one so often hears of (often Realtor7-induced) panic-selling by whites after (often Realtor-induced) blockbusting. It’s interesting to consider into whose pocket the money left on the table by the white panic-sellers through this kind of market distortion goes. With panic-selling I’d assumed (with some evidence) that white Realtors and black real-estate agents8 split the profits between them through some kind of a middle-man arrangement. So evidently there wasn’t panic-selling going on in Baldwin Hills. This is consistent with the outline given by Darnell Hunt, editor of the essential (although somewhat uneven in readability, as such academic ventures characteristically are) volume Black Los Angeles:

If white flight from Baldwin Hills was only tangentially related to the blockbusting which took place in the flats in the aftermath of Shelley v. Kraemer, then, it makes sense that white homeowners, not in so much of a state of panic, would have been able to take personal advantage of the price differential created by a distorted market which wouldn’t allow black professionals to buy in Beverly Hills, e.g., but left Baldwin Hills open to them. A panic would no doubt have ensued towards the end of the racial transition, but it’s entirely plausible that a chronologically drawn-out process would have left less room for profiteering by real-estate professionals. It’s always interesting to see academic ex-post-facto sources confirmed by contemporary primary sources, not least when the contemporary primary source is also an excellent thriller!

Finally, let’s move on to the actual plot. There’s a conspiracy. I’m not going to tell you what it is. Read the book. But in his introduction to the Old School Books reprint, Jefferson compares his plot to

…the startling revelation that the CIA may well have been deeply implicated in the importation, distribution, and sales of “crack” cocaine targeted exclusively for African-American-dominated inner cities as a way of financing the government’s support of the Nicaraguan Contras.

10

I think conspiracy theory adherence is one of the most segregated areas of American public life. For instance, in November 2014 I, along with some of my colleagues, attended (and wrote about) the Los Angeles premiere of a documentary on serial killer Lonnie Franklin. During the Q&A, star Pam Brooks condemned this CIA-cocaine-Contra conspiracy and was cheered by most of the black audience while the white audience was mostly quiet. White people will, in my experience, almost uniformly, reflexively dismiss the plausibility of this particular conspiracy theory.

It’s possible that they’ll do the same with the conspiracy at the heart of Jefferson’s novel, but that’d be a shame. While Jefferson’s fictionalized conspiracy is certainly fictional, it has the same symbolic explanatory force that all good conspiracy theories must have to survive and thrive as memes, e.g. that the mafia killed JFK or the imagined problems with Barack Obama’s citizenship. In any case, whether you read it as a plain thriller, a vivid window into 1970s Los Angeles, social commentary, or some combination of those, I highly recommend that you read it.

- We made up this term but really, it should have been made up before now. If these literature professors weren’t such lazy sons-a-bitches it certainly would have been already. It translates roughly as “Novel of locals” and we mean it to refer to novels that can only really truly be understood by locals, no matter how attractive they might be to non-locals.2 Raymond Chandler wrote romans des riverains, as did Charles Dickens. It seems that if one is a local in one spatiotemporal locality, one gains the ability to recognize romans des riverains associated with other spatiotemporal localities, even if one lacks the ability to fully comprehend the localisms. I haven’t tested this theory scientifically, but when I read Dickens I see hard-core localism (riverainité?) everywhere. It’s a not insignificant part of the pleasure I find in his work.

- If I were writing a roman des riverains based in 1970s Los Angeles here instead of doing whatever it is that I’m doing, instead of “non-locals” I’d say “vals.” If you don’t know what that means, you’re not a riverain. If you do know what it means you can probably locate my childhood home to within a mile in space and a decade in time.

- P.66 of the Old School Books edition.

- This passage is from the “‘Go’ Places” column of the Sentinel, which is super-fun to browse through old installments of. You can search for it here with your paid-up Los Angeles Public Library subscription.

- Between approximately 1962 and 1972 by our calculations.

- P.36 of the Old School Books edition.

- Do you wonder why the word “Realtor” is capitalized? There’s a reason, which my colleagues will, they claim, be discussing here soonest. You can figure it out yourself easily enough, though. And notice that even the L.A. Times sticks to this convention, long after they’ve given up on other such genericized trademarks like Heroin™ and Aspirin™.

- Black people weren’t welcome to become Realtors until fairly recently, although they could certainly be real-estate agents.

- Black Los Angeles. Darnell Hunt, Ana-Christina Ramón (eds). New York University Press 2010, p. 9.

- P.11 of the Old School Books edition.

- If that link’s not working for you, the cite is: ‘NAME OF THE GAME’ SLAYING UNDER PROBE: ‘Manager’s Story just Didn’t Jibe.’ Los Angeles Sentinel, 29 Mar 1973: A1.

Cover image of book appears under the fair use doctrine, don’t it? Image of Cyrano building is deep-linked-to, which takes care of our liability. It ultimately seems to be owned by the Marina Del Rey Historical Society, if such a thing as the history of Marina Del Rey can actually be said to exist. The Cyrano advertisement appears here under a claim of fair use as well as a feeling that there’s no one left holding the copyright. I suppose we’ll see, eh? Image of Baldwin Hills office building is released under the CC BY-SA 3.0 by its creator and you can get it from Wikimedia. Cover of Black Los Angeles appears here under a fair use claim.

Read Dr Jefferson’s followup novel to 103rd Street titled ALICE IN DREAMLAND.

https://aalbc.com/books/bookcover.php?isbn13=9780578894799