In his 2017 rush to destroy Parker Center, not only did José Huizar direct his staff to organize a series of phony performances of public support at various hearings as part of a twisted quid pro quo deal with various Little Tokyo luminaries, but on February 13, 2017 or thereabouts his office also violated California’s open meeting law, the Brown Act, by polling all the other Council offices on how they intended to vote the next day on the designation of the building as a historic-cultural monument.

In his 2017 rush to destroy Parker Center, not only did José Huizar direct his staff to organize a series of phony performances of public support at various hearings as part of a twisted quid pro quo deal with various Little Tokyo luminaries, but on February 13, 2017 or thereabouts his office also violated California’s open meeting law, the Brown Act, by polling all the other Council offices on how they intended to vote the next day on the designation of the building as a historic-cultural monument.

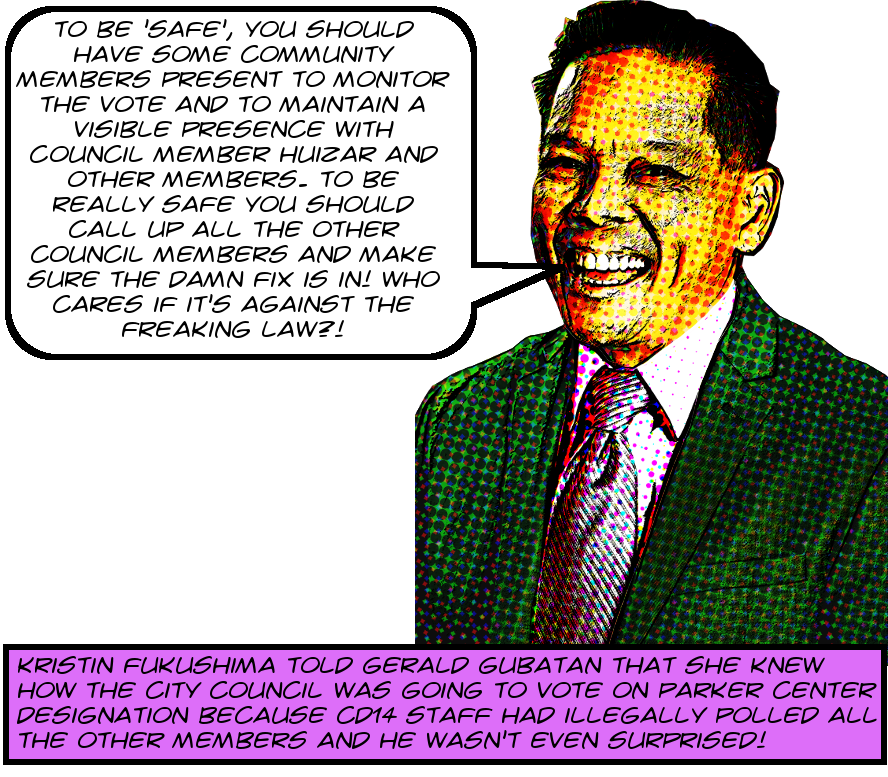

The evidence is right here in this email conversation between Kristin Fukushima, Little Tokyo anti-Parker-Center coconspirator, and Gerald Gubatan, who is Gil Cedillo’s planning director:1

On Mon, Feb 13, 2017 at 2:03 PM, Kristin Fukushima <kristin@littletokyola.org> wrote:

Hi everyone,

Gerald, just letting you know – I spoke with CD 14 this morning, and apparently they checked in with all the offices and have confirmed that they are expecting everyone on City Council tomorrow to vote in approval of PLUM’s recommendation against HCM nomination for Parker Center. To be safe, a handful of us will still be there tomorrow, but good news nonetheless!

Thanks!

If she’s telling the truth about CD14 checking in with all the offices, and why would she not be, then the City Council violated the Brown Act by holding a meeting that the public had no access to. It’s not surprising, of course. We’ve seen significant circumstantial evidence that such violations happen regularly, but man, has it been hard to claw that proof out of the City.2

This kind of lawless behavior in no way seems uncharacteristic of Huizar. It wouldn’t have seemed so even before his enormous capacity for lawlessness and illicitry was made even more manifest than anyone could have expected.3 Sadly, there’s nothing at all to be done about it at this point. The Brown Act has very short built-in time limitations for taking action, and this is far past all of them.

By the way, it may not seem obvious that a staff member from one Council office contacting all the other offices and asking how they’re planning to vote on an agenda item constitutes a meeting, but it’s clear under the law that it does. For all the wonky details, laid out in full wonky splendor, turn the page. You know you wanna!

To see the problem we start with the Brown Act at §54952.2(b), which states:

A majority of the members of a legislative body shall not, outside a meeting authorized by this chapter, use a series of communications of any kind, directly or through intermediaries, to discuss, deliberate, or take action on any item of business that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the legislative body.

The scope of the prohibition here is not necessarily that clear. As you can well imagine, these legislative bodies4 are a bunch of sneaky bastards, and have probed, tested, and exploited every possible loophole to find ways to conduct their work in secret. For instance, an obvious way for a majority to confer and yet, perhaps, not trigger the prohibition, is to designate one member to talk to all the other members one on one. This way no more than two meet at a time, which is not generally a majority.

But judges aren’t dumb, at least not mostly, and they’re definitely onto such shenanigans. This kind of event is called a serial meeting, and it counts the same as an ordinary meeting under the law. In other words it’s banned if it ultimately involves a majority. Likewise, as the law says, it’s not allowed to use intermediaries to get away with a serial meeting. The California Attorney General publishes an extraordinarily useful guide to the Brown Act, and here’s one thing it has to say about serial meetings:

… when a person acts as the hub of a wheel (member A) and communicates individually with the various spokes (members B and C), a serial meeting has occurred. In addition, a serial meeting occurs when intermediaries for board members have a meeting to discuss issues. For example, when a representative of member A meets with representatives of members B and C to discuss an agenda item, the members have conducted a serial meeting through their representatives as intermediaries.

And that’s just what happened here. Someone from Huizar’s office checked in with all the other Council offices to see how they were voting. Bam! Serial meeting! Oh, but the law is subtle. It’s actually not intrinsically illegal for one Council staffer to call up all the other Council offices just in itself. In order to violation §54952.2(b) they also have to “discuss, deliberate, or take action on any item of business that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the legislative body.”

And it’s plausible, anyway, that a staffer from CD14 checking in with all the other Council offices isn’t enough of a discussion or deliberation to trigger the prohibition. But it’s also plausible that it is. And in fact it is enough. The California Court of Appeals has said so in Stockton Newspapers, Inc. v. Redevelopment Agency (1985), a case which is almost eerie in its similarity to the situation with CD14. Here’s how the court summarized the facts in that case. The defendants are the members of a legislative body:

Gerald Sperry is the attorney for the redevelopment agency. The complaint alleges that on the same day, “each of the defendants … participated in a one-to-one telephonic poll initiated by … Sperry … for the purpose of obtaining a collective commitment or promise by said defendants to approve the transfer of ownership” of real property forming part of a planned waterfront development. As might be expected, this telephonic poll was not conducted at either a regular or special meeting of the legislative body of the agency nor was plaintiff or the public given notice of it.

After a review of the legislative and judicial history5 the court concludes:

The foregoing authorities make clear that the concept of “meeting” under the Brown Act comprehends informal sessions at which a legislative body commits itself collectively to a particular future decision concerning the public business. … Accordingly, we conclude that a series of telephone conversations conducted through an intermediary may, under a liberal construction of the circumstances here pled, constitute a meeting of the legislative body within the scope of the Brown Act.

And that, friends, is the story of yet another violation of yet another law by yet another Los Angeles City Councilmember!6

Image of Gerald Gubatan is ©2019 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and also why not look over here for a lil seccie?

- For a detailed discussion of the rest of this conversation, take a look at this recent post on the manufacturing of community buy-in in favor of demolishing Parker Center.

- It’s probably not coincidence that, rather than coming from the City, this email was part of a large production from the Little Tokyo BID, whose lawyer, Yuriko Shikai, basically trained herself to handle CPRA requests by researching my objections to her bizarro-world reasoning, only to find every single time that I was correct. That and handling Katherine McNenny’s writ petition against the BID. I feel like she owes us some money for CLE or something.

- Not more manifest than anyone could have expected he might have been up to. Anyone who was paying attention to the guy would have expected as much and much, much more. But more manifest than anyone could have expected would be made manifest, and in such a pleasingly florid manner, too! If you’re living in the worst of times this is the kind of thing that counts as the best of times! If my WordPress footnote plugin, Easy Footnotes, which by the way I adore and highly recommend, allowed me to put footnotes inside footnotes, I’d put one here shouting out the brilliant Mr. Dickens, whose famous line I’m shamelessly remixing for my own paltry purposes. Unlike many books that are known mostly for one or two famous bits, the rest of this one is as good or better.

- Which is a term of art in the Brown Act world, basically meaning any group that’s subject to the Brown Act. Definitely City Councils, most committees, and the boards of directors of business improvement districts, to name a few which are of essential importance to the work of this blog.

- Which is really interesting and really worth your time to read.

- I’m skipping the issue of who actually broke the law here. It’s not especially clear to me, but the Court of Appeals in the quoted case found that the members of the legislative body were the lawbreakers. It’s got to be the same in this case, but the threads are too tangled for an amateur like me to be able to explain why.