Senator Maria Elena Durazo filed SB-749, amending the California Public Records Act, last month, but it was only on Wednesday that it was amended away from a placeholder. The fleshed-out bill addresses two problems with the California Public Records Act.

Senator Maria Elena Durazo filed SB-749, amending the California Public Records Act, last month, but it was only on Wednesday that it was amended away from a placeholder. The fleshed-out bill addresses two problems with the California Public Records Act.

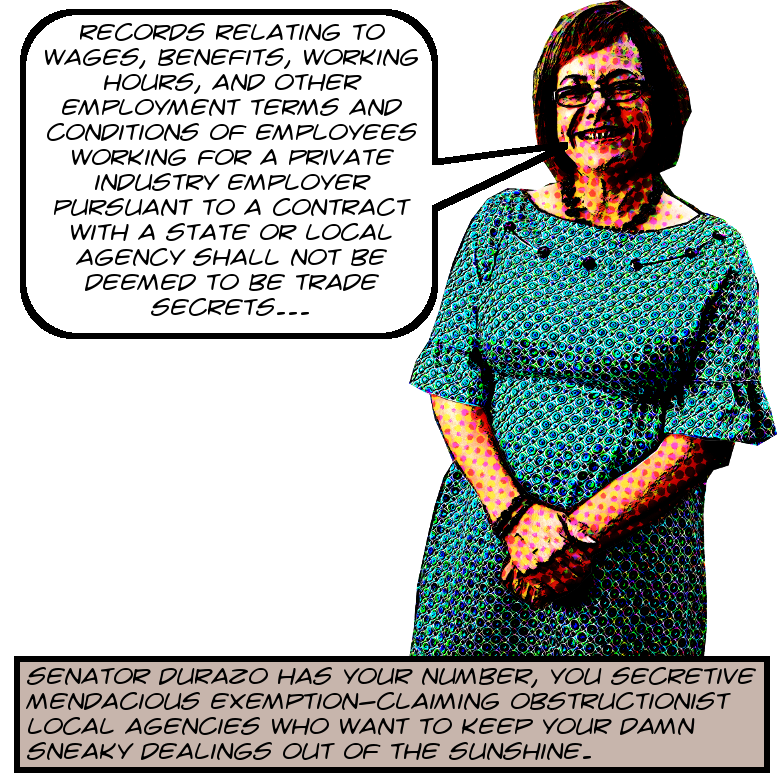

First, it would state that “records relating to wages, benefits, working hours, and other employment terms and conditions of employees working for a private industry employer pursuant to a contract with a state or local agency shall not be deemed to be trade secrets under the act.” In my experience it’s fairly common for local agencies to claim that records like this are exempt. Sometimes they claim that they’re trade secrets1 and sometimes that they’re material found in personnel files.2

That last claim is pretty clearly bogus, so probably the more serious obstructionists rely more on claims of trade secrets. For instance I had this happen to me with the Fashion District BID in the person of Rena Leddy, who refused to tell me the hourly rates of the BID’s renewal consultant, Urban Place Consulting. That is, until a kindly lawyer sent them a not-so-kindly demand letter on my behalf. Then they coughed the goods right up.3 So if the bill passes with this bit intact they won’t be able to do that any more, and the personnel file claim is functionally a non-starter, so that’ll be good.

Incidentally, while I understand the danger of letting the perfect be an enemy to the good, I would still just like to say that the problem being solved here is at best a minor particular instance of a much larger family of problems involving records owned by private contractors who are working for public agencies. That is, that the agencies can write the contracts so that the contractor owns the records and the agency explicitly does not have access to them.

The Hollywood Property Owners’ Alliance famously did exactly this in 2016 with the Andrews International BID Patrol. Kerry Morrison even admitted under oath that the purpose of the change was to thwart my CPRA requests. And the judge ruled that it was allowable under California law for them to do this, and even to make the change retroactive.

But such is not the law in every state. For instance, Florida Statutes section 119.0701 makes pretty much all records generated by private contractors subject to the CPRA if they relate to work done for a public agency. It’s a really powerful, really beautiful statute. We need a version here, and this bill is not it. But it’s not bad.

The second issue addressed by Durazo’s bill has to do with reverse CPRA actions. In these suits a third party, e.g. a police union, sues to prevent a public agency from releasing records to a requester. The Court of Appeal held last year that the third party is liable for the requester’s fees if they lose, and this bill would formalize that finding by putting it into the statute. The bill also requires that the requester be brought into a reverse CPRA action as a party, I assume so that the case can’t be heard without the requester’s input.

And finally, and this may be the most powerful part, the law would forbid a court from ordering that a record be withheld if the order is based on a discretionary exemption. But most of the exemptions are discretionary. In fact I kind of think that all of them are, but maybe there’s something I don’t understand. This clause alone will make it harder to win reverse CPRA actions, as it should be. Turn the page for a transcription of the legislative counsel’s digest and the proposed new statutory language.

Legislative Counsel’s Digest

The California Public Records Act requires state and local agencies to make their records available for public inspection, unless an exemption from disclosure applies. Existing law provides that nothing in the act requires the disclosure of corporate proprietary information including trade secrets, among other things.

This bill would provide that records relating to wages, benefits, working hours, and other employment terms and conditions of employees working for a private industry employer pursuant to a contract with a state or local agency shall not be deemed to be trade secrets under the act. The bill would also provide that records of compliance with local, state, or federal domestic content requirements and records of a private industry employer’s compliance with job creation, job quality, or job retention obligations contained in a contract or agreement with a state or local agency shall not be deemed trade secrets under the act.

Under existing law, a person may seek injunctive or declaratory relief or a writ of mandate to enforce their right to inspect or receive a copy of a public record, as specified. Under existing case law, an agency’s decision to release a public record pursuant to the California Public Records Act is reviewable by a petition for a writ of mandate on the basis that the public record was confidential, which is known as a reverse public records act.

This bill would require the requester, as defined, to be named as a real party in interest in a reverse public records action, and would require a court to allow the requester to participate fully on the merits of the reverse public records action. The bill would require the person who initiated the reverse public records action to pay the requester’s court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees if the court denies the petition seeking to prevent the public agency from disclosing the record at issue. The bill would require a public agency to pay court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees to the requester under specified circumstances.

The California Constitution requires local agencies, for the purpose of ensuring public access to the meetings of public bodies and the writings of public officials and agencies, to comply with a statutory enactment that amends or enacts laws relating to public records or open meetings and contains findings demonstrating that the enactment furthers the constitutional requirements relating to this purpose.

This bill would make legislative findings to that effect.

The people of the state of California do enact as follows:

SECTION 1. Section 6254.34 is added to the Government Code, to read:

6254.34. (a) Notwithstanding any other law, records of wages, benefits, working hours, and other employment terms and conditions of employees working for a private industry employer, or a subcontractor of a private industry employer, pursuant to a contract with a state or local agency are not trade secrets and are public records for purposes of this chapter, except that nothing in this section requires the disclosure of the names and other personally identifying information of employees if that information is otherwise exempt from disclosure pursuant to the provisions of this chapter.

(b) Notwithstanding any other law, records of compliance with domestic content requirements specified in Section 5323(j) of Title 49 of the United States Code, or with any state or local law mandating domestic content in state or local agency procurement or limiting or prohibiting the use of articles, materials, or supplies mined, produced, or manufactured in foreign countries, are public records and are not trade secrets for purposes of this chapter.

(c) Notwithstanding any other law, records of a private industry employer’s compliance with job creation, job quality, or job retention obligations in a contract or agreement with a state or local agency or pursuant to a state or local law are not trade secrets and are public records for purposes of this chapter.

SEC. 2. Section 6259.5 is added to the Government Code, to read:

6259.5. (a) In any reverse public records action, the following requirements apply:

(1) The requestor shall be named as a real party in interest in the proceeding, and the person who initiated the reverse public records action shall serve a copy of any pleading on the requestor. If the person who initiated the action does not provide the court with proof of service upon the requestor, the court shall dismiss the reverse public records action with prejudice.

(2) If the requestor wishes, the court shall allow the requestor to participate fully on the merits of the reverse public records action.

(3) A person who files a reverse public records action shall label the action as such on the first page of the pleadings.

(4) A court may not base an order prohibiting the public agency from disclosing the record on the discretionary exceptions to disclosure set forth in Section 6254.

(b) (1) In a reverse public records action, if the court denies the petition seeking to prevent the public agency from disclosing the record that is at issue, the court shall order the person who initiated the reverse public records action to pay the requestor’s court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees. If the court finds that the public agency delayed disclosure of the record to facilitate the filing of the reverse public records action, or if the public agency declined to defend its position that the record was subject to disclosure in the reverse public records action, the court shall order the public entity to pay court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees to the requestor.

(2) In a reverse public records action, if the court orders the public agency to not disclose the record that is at issue, the court shall not order the requestor to pay court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees to the third party who filed the reverse public records action or to the public agency.

(c) For purposes of this section, the following terms have the following meanings:

(1) “Requestor” means the person who requested the record that is the subject of the reverse public records action.

(2) “Reverse public records action” means a petition for a writ of mandate pursuant to Section 1085 of the Code of Civil Procedure seeking declaratory or injunctive relief that requests that court enjoin a decision by a public agency to disclose a record in response to a request by a requestor.

SEC. 3. The Legislature finds and declares that Sections 1 and 2 of this act, which add Sections 6254.34 and 6259.5 to the Government Code, further, within the meaning of paragraph (7) of subdivision (b) of Section 3 of Article I of the California Constitution, the purposes of that constitutional section as it relates to the right of public access to the meetings of local public bodies or the writings of local public officials and local agencies. Pursuant to paragraph (7) of subdivision (b) of Section 3 of Article I of the California Constitution, the Legislature makes the following findings:

It is in the public interest to ensure that the records identified in Section 1 of this act are not considered trade secrets and are subject to disclosure under the California Public Records Act and to ensure that reverse public records actions are conducted in a manner that adequately protects the public’s right of access to public records.

Image of Senator Maria Elena Durazo is ©2019 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and here is roughly what it started out in the world as.

- The exemption for trade secrets comes into the CPRA via section 6254(k), which brings in a whole host of exemptions based on various privileges elsewhere in the California Code. I’m sorry but I’m just too lazy to track down the trade secrets privilege which is incorporated into the CPRA via this section.

- This kind of stuff is partially exempted by section 6254(c).

- Tangentially, Urban Place Consulting isn’t just a renewal consultant. They also manage a couple of BIDs in the City of Los Angeles, which are the North Hollywood BID and the Figueroa Corridor BID. A couple years ago I was doing a CPRA or two on these BIDs and the feet-on-the-ground staff boy, Aaron Aulenta, spent months black-markerizing all the salaries of all the security guards. He claimed it was per the personnel file exemption. And I tried to argue with him, even though I could read the salaries through the marker, but he ignored me. Then later he got too lazy to keep it up and stopped redacting anything. And so it goes.