All over the State of California local agencies are using the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse to deny the public access to records. I don’t, therefore, have nearly as much material to write about so in response I’m writing about the lack of records instead, and the various ways agencies deny access. Here are the first and also the second posts in this series, and you’re reading the third!

All over the State of California local agencies are using the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse to deny the public access to records. I don’t, therefore, have nearly as much material to write about so in response I’m writing about the lack of records instead, and the various ways agencies deny access. Here are the first and also the second posts in this series, and you’re reading the third!

For more than six months now I’ve been looking into the question of why Uber and Lyft premium services, the ones that approximate limousines, I guess, continued to be allowed to pick up passengers at curbside in LAX even after October 2019 when the airport banned taxis and regular Uber/Lyft drivers, relegating them to a special off-site pickup lot. The matter first came to my attention via this October 29, 2019 Spike Friedman tweet and I sent them this request that same day. And as is typically the case the process is taking forever, although a little bit of information has dribbled out.

In February of this year e.g. LAX, in the person of Supreme Operations Commander Angela Jamison, produced a few emails, only one of which related to the question. This email, from Landside1 Management staffer Shirlene Sue, seems to be an answer to Jamison’s request for records responsive to my request. It basically says that Uber/Lyft premium services operate under different rules from regular Uber/Lyft and taxis and that’s why. It’s also worth noting that I made the request in October 2019 and Jamison sent me these three emails four months later. That’s more than a month per email.

Of course, the explanatory power of this statement is nil — essentially all it says is that they’re allowed to pick up passengers at the curb because the rules allow them to pick up passengers at the curb. It tells us nothing about how or why the decision was made. But Jamison claimed that these three emails were the only records responsive to my request (ridiculous color scheming in original; blue is from my request, red is Jamison’s response):

Subject: CPRA request (LAWA.2019.10.29.b)

From: “JAMISON, ANGELA M.”

Date: 2/17/20, 5:04 PM

To: “■■■■■■■■■@■■■■■■■■■.■■■” <■■■■■■■■■@■■■■■■■■■.■■■>

CC: PublicRecordsRequest

■■■■■■■■■,

Thank you for your patience as we identified responsive documents to your public records request dated 10/29/2019. Attached you will find the documents we were able to identify as responsive. Thank you.

1. A copy of the policy itself.

– We have identified no responsive documents.

2. Emails from the salient time span that are between LAWA and people at any company providing passenger pickup that’s still allowed to pick up inside the airport.

– An email (sample attached) was sent to TCP operators, charter bus operators, scheduled bus operators, hotel/motel shuttle operators, and private parking operators.

3. Minutes, notes, agendas of meetings where this matter was discussed. Recordings of such meetings if recordings exist.

– We have identified no responsive documents.

4. Internal LAWA emails discussing this aspect of the policy.

– We found one attached email that helps explain the issue.

Angela Jamison

Program Manager – Strategic Operations

Airport Operations and Emergency Management

Los Angeles World Airports

(: 424.646.9108 | *: ajamison@lawa.org

Cell: 513.633.8627

This is precisely the kind of carelessly implausible nonsense that so often passes for a response to a CPRA request in the City of Los Angeles. LA-Xit was a major policy shift for LAWA. It was in the news for months. The City Council discussed it repeatedly. Both Uber and Lyft were directly affected by it. And yet Jamison claims that LAWA does not have a copy of the policy. That no emails were exchanged between anyone at LAWA and anyone at either Uber or Lyft about which of their cars would be allowed to continue to pick up passengers curbside. That this topic was never discussed at a meeting.

And even though Jamison did provide that email from Sue explaining the policy, that was from December 2019 and was generated in response to my request. So Jamison is also claiming that no one at LAWA ever discussed this curbside pickup policy in an email. This cannot possibly be true. Nothing of this magnitude happens in a bureaucracy the size of LAWA by accident, without discussion. No such discussion fails to leave a trace. And Jamison doesn’t even care to make her claims plausible.2

And one problem with pressing Jamison on this issue, or with pressing any public official when they say that responsive records don’t exist, is that we members of the public generally have no independent way of knowing for sure what the truth is. There might legitimately be no records or the official might be lying or, maybe more likely, interpreting the request in such a ludicrously strict way that it’s technically true that there aren’t responsive records but actually there are plenty.3

This apparently occurred to the legislature, though, because the CPRA at §6253.1(a) requires officials to “to assist the member of the public [to] make a focused and effective request that reasonably describes an identifiable record or records”. And officials really, really hate doing this but the law says they gotta, so I hit up Jamison for some help:4

None of these records address the question, though, which is why TCP operators pick up inside the airport. Did that just happen by magic or did someone decide it when LAXit was being planned? If the latter, which I suspect is more likely, surely there’s some written trace of the decision.

Please assist me, therefore, in overcoming the practical obstacles in obtaining these records which, as the law allows, I’ve described by content.

Now, it later came out that Jamison had spent at least part of that four months between request and production consulting with the LA City Attorney about the request. But she didn’t see any need to consult with anyone about assisting me. She didn’t want to assist me and therefore concluded that she didn’t have to assist me, which is clear from her response: “LAWA does not have any documents that are responsive other than what we sent.”

She sent that response so fast, and it was so formulaic, that it’s reasonable to conclude that the response was not only hasty and not sent in consultation with the City Attorney, but petulant as well. In any case it’s really, really obvious that an operation the size and complexity of LAWA didn’t make this decision, or any decision, without it ever being mentioned at a meeting.

Thus did I reply to Jamison with a little more pressure, asking her to not only to assure me that she’d checked all potentially relevant agendas and minutes but that she’d also send me copies so I could check for myself. Another two weeks went by and then on March 2, 2020 Jamison responded, claiming yet again that this decision, to allow premium car services to continue to pick up passengers at curbside, was reflected nowhere in any public records.

In this response she ignored my request for the agendas and minutes even though the CPRA required a response after only 10 days.5 So I pressed her for a response that satisfied the CPRA’s requirements. Either produce the minutes and agendas, say when they’ll be ready, or cite an exemption authorizing a denial. A few days later, on March 4, 2020, she agreed to produce.

Here’s where we’re at on this so far. On October 29, 2019 I sent LAWA a simple CPRA request about a matter of pressing public importance. By February 2020, four months later, LAWA had produced nothing useful, claimed that nothing useful existed, and asserted that their response was complete. After some quibbling, by March 3, 2020, they agreed to provide a few more records. It’s now three months after that, more than seven months after my request, and we still don’t have an answer to the question.

There’s a lot more to this story, though, and it’s not over even now, but it’s going to have to wait till Part II, because it’s all a lot more complex than I realized when I set out to write this. I would like to say, though, that this episode is a very typical example of the ways in which local governments make the CPRA almost impossible to use. They don’t ever exactly refuse to follow it. Instead they stall, they deny, they say they’ve done extensive searches when in fact they have not, and so on. They argue at every stage, take weeks in between answers, and so on.

The only recourse the CPRA allows to enforce it is a lawsuit, but it only allows a lawsuit if an agency actually denies access to records. To sue under circumstances like this is kind of tricky since it’s necessary to make the case that the agency’s temporizing amounts to a denial of access. It’s worse when they say records don’t exist because judges will believe them. And as soon as someone files a suit they, at least in the City of Los Angeles exclusive of LAPD, usually settle immediately.

And there aren’t easily imposed consequences for basically forcing a suit and then capitulating immediately, either. A lot of these problems can be solved through local legislation, which we badly, badly need in Los Angeles. Anyway, stay tuned for Part II, in which we encounter one of the most weirdly wrong applications of a CPRA exemption I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen an awful damn lot of weirdly wrong ones!6

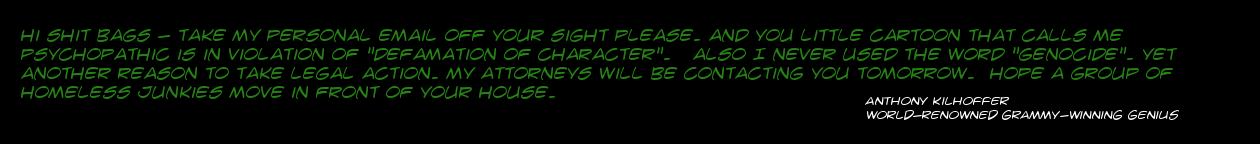

Image of LAWA staffer ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■ is ©2020 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■!!!!

- Operations at LAX, and maybe at every airport in the universe for all I know about it, are divided into Airside, Landside, and Terminals.

- One of the tragical aspects of this response is that, as common and as completely unbelievable as it is, a judge will most likely buy it completely. If this particular aspect of the matter were to be litigated, and there are aspects of this matter that will probably end up in court but this particular bit probably isn’t one of them, it’s exceedingly easy to imagine a judge holding that because Jamison said under oath that no such records existed it’s not possible to conclude that the search was inadequate. I’ve had e.g. board members of business improvement districts claim in 15 word-for-word identical depositions that they delete their emails directly after either reading or sending them. Which is not only obviously a lie but it’s a stupid, arrogant, in-your-face lie. And the judge even said that the claims were implausible, and he even said that it was weird that all 15 of the declarations were verbatim copies, but nevertheless he was not willing to discount this sworn evidence on the basis of his suspicions. Which, for all I know, is the right result under California Civil Procedure, but it certainly does explain the willingness of public agencies to lie like this, and to lie so carelessly. Nothing will come of it.

- In this context the word “technically” means, as usual, that a judge might well decide that there were in fact responsive records but there’s not enough evidence to establish definitively that the official was consciously lying. In my experience judges will generally actually go with the evidence but they won’t hamper what they, upholders of the power structure, see as the legitimate and necessary functioning of government by using common sense to take them even one jot, tittle, or iota beyond it into interpretation.

- II’m not just imagining that they hate it. I was recently lucky enough to get a chance to listen to Christine Wood, a lawyer from Best, Best, and Krieger, a law firm specializing in helping public agencies evade their duties under the CPRA (although they don’t precisely describe themselves that way!), who used to run LAUSD’s CPRA unit, actually state out loud in a webinar that when she worked for the public she used to hate having to help requesters. She also said that she’d lately realized that the clause could be leveraged against requesters (my summary) and that she’d describe how later but she never got around to it.

- It’s worth noting here that there is no such thing in the law as a “formal” CPRA request. The mere act of asking to see some records is a request as regulated by the CPRA. It’s not even required to invoke the CPRA for the CPRA’s requirements to apply. Thus, e.g., if you’re in a public office and you see some stuff on a desk you want to look at just ask for it. They’re obligated to either let you see it or deny you according to the requirements of the law. This is especially interesting when the stuff is records responsive to someone else’s CPRA request. Since they’ve already prepped it for release they can’t even claim that they need to review it before they show it to you. The law requires them to let you look at it right then. Just for instance, in October 2019 I did this very thing in CD14. I saw some records made ready for LA Times reporter Dakota Smith, I asked the receptionist if I could take a look a them and he went to check with his boss. The boss, Huizar’s astonishingly clueless and perennially pissed-off-although-maybe-mostly-at-me-but-I-doubt-it communications deputy Yves Martin denied me access. Apparently he checked with the City Attorney, who set him straight, so the next week I went in to look at Smith’s records only to learn that Huizar’s new policy was to keep public records behind a folding screen and out of sight of the public to prevent this situation from arising again. Never fear, though. Just remember to ask the receptionist to see all public records they currently have ready to produce to anyone. Then the law requires them to look behind the screen!

- And also to find out what the cartoon is about, because I made it before I realized that I was going to have to break this sucker in two.