It occurred to me that maybe you might want a link to the petition right away without having to read through this whole damn blog post to get to it at the end. If so, here is a link to the petition!

It occurred to me that maybe you might want a link to the petition right away without having to read through this whole damn blog post to get to it at the end. If so, here is a link to the petition!

The Office of the City Attorney of Los Angeles has a thing called the Citywide Nuisance Abatement Program, or CNAP,1 in which they use various civil laws to have tenants or property owners declared nuisances and evicted, required to put up security cameras and allow LAPD warrantless access to them, or other such conditions.

Often allegations of gang activity are involved. So just for instance, there’s this case against the Chesapeake Apartments on Obama Blvd between La Brea and Crenshaw. Or this smaller scale one against a woman with a house near 52nd and Vermont. Or this against a small apartment building near 56th and Western.

Most famously this year the City Attorney has been relentlessly pursuing such an action against Slauson and Crenshaw Ventures LLC, owned by the late Nipsey Hussle and his partner David Gross. The allegations against Hussle and Gross’s property seemed unsupported by evidence, though, and this is apparently not unusual.

This program and others like it have long been understood as part of the gentrification machine, particularly pernicious in Los Angeles. That is, the City can drive out tenants in rent stabilized apartments, or force property owners to install cameras and give LAPD unfettered access to them, or impose various other conditions to serve their ends. This lets landlords raise rents or forces residents to become essentially LAPD informants.

These civil actions also, like gang injunctions, contribute to the City’s general program of harassing and controlling non-white citizens, not unusually in support of ongoing gentrification. They’ve been the subject of a great deal of academic attention.2 Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer filed almost a hundred of these in the four years following his 2013 election and since a federal judge in 2018 invalidated the City’s gang injunction program, I expect the rate of nuisance actions to have increased substantially.

And court actions generate a lot of records, and records are what we live for around here! I was able to get the City Attorney to cough up almost 70 actions filed between 2017 and 2019, and I have other requests out for earlier complaints. But it also seems important to get the demand letters which must precede these actions.

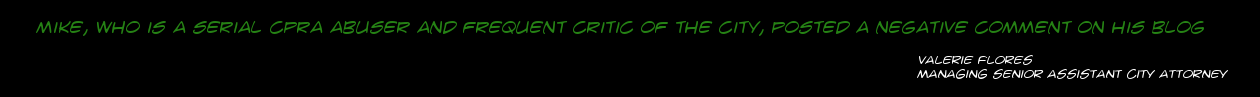

For one thing there must be more of them. After all, not every demand letter leads to the courthouse. Thus the letters would be essential for understanding the scope of the program, who’s targeted, some clues as to how targets are chosen, and so on. And that is how I came, on August 5, 2019, to fire off this CPRA request to the City Attorney, asking for among other things, these letters from 2018 and 2019.3

And I wasn’t surprised when the City denied my request with the usual series of vague and unelaborated exemption claims:

The City generally withholds nuisance abatement letters as exempt from disclosure under Government Code sections 6254(f), 6254(k), and 6255. … [The City] will deny your request to obtain the other nuisance abatement letters issued over the past two years, as such letters are exempt from disclosure for the reasons previously stated.

But really, this is all nonsense, and I sent them another email explaining why. The basis of their first exemption claim is the CPRA at §6254(f). This is the so-called “investigative materials” exemption, which basically allows agencies to withhold records of investigations, complaints, intelligence information, and security files. Obviously these letters are none of these things.

The basis of their second claim is the CPRA at §6255(k). This exemption includes all privileges granted by the evidence code and a bunch of other similar things. So e.g. this incorporates the attorney client privilege, the trade secrets privilege, and so on. But the key thing about this exemption is that it only draws a bunch of other exemptions into the law. It’s not in itself an exemption, so without specifying which incorporated exemption is being invoked it’s not possible to dispute it.

And the basis of their third claim is the infamous catch-all exemption, found at §6255(a), which allows agencies to withhold records when “on the facts of the particular case the public interest served by not disclosing the record clearly outweighs the public interest served by disclosure of the record.” The law requires the claiming agency to justify the public interest weighing test here, which the City refused to do. So all that is why, last week, attorneys Ian Stringham and Tasha Hill filed this petition against the City. Stay tuned for what happens next!

- Pronounced SEE NAP.

- Not a bad place to dive into which is this fine article by Ethan Silverstein from the Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment.

- Not that I don’t want them all. Of course I do. But if one expects a request to be denied it is often good to strictly limit the time period in order to keep the respondent from denying the request on the basis of there being too many responsive records. If the time period is short and the agency’s going to deny they’ll be much more likely to deny on some substantial basis, which can then usually be challenged more effectively than your garden variety 6255(a)-based claim that there are too darn many records to handle.