UPDATE: This hearing has been changed to February 4, 2019 at 8:30 a.m. The trial has been reset as well. The new dates are set here in this order.

UPDATE: This hearing has been changed to February 4, 2019 at 8:30 a.m. The trial has been reset as well. The new dates are set here in this order.

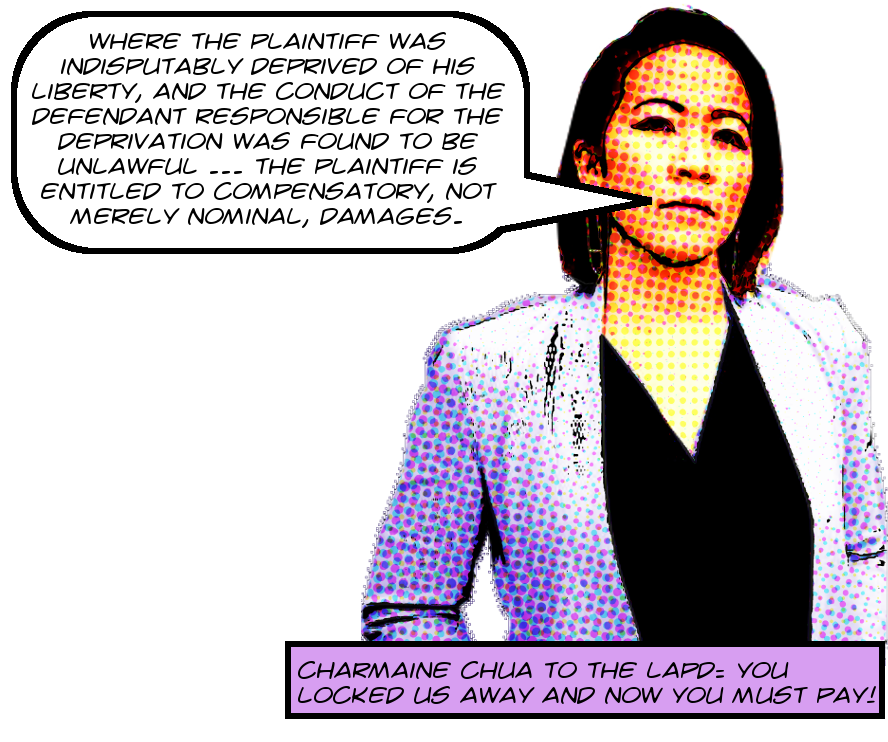

Almost three years ago now, in January 2016, Charmaine Chua and others sued the City of Los Angeles for civil rights violations arising from 2014 protests over the killing of Michael Brown in 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri. In May 2017 the case was certified as a class action, but it seems like not that much has happened since then, I guess maybe because it still seemed like there was some chance that it might settle.

Well, evidently that’s not going to happen, and the case is revving up again. In September of this year Judge John Kronstadt issued a scheduling order which, in part and barring settlement, which didn’t happen, ordered the plaintiffs ” to file a motion (“Motion”) for leave to present claims of alleged general damages on a classwide basis at trial of the corresponding claims for liability, which shall include a proposed trial plan for the presentation of evidence as to such alleged damages.”

I guess the point is that usually in a lawsuit the plaintiff can get damages to make up for what the defendant’s conduct cost them but if they’re suing for so-called general damages, where no specific objective dollar value can be assigned, it’s necessary to argue that such payments are appropriate. Anyway, as always, I’m not a lawyer, but that seems to be what the motion, filed by plaintiffs on November 5, 2018, seems to be arguing.1

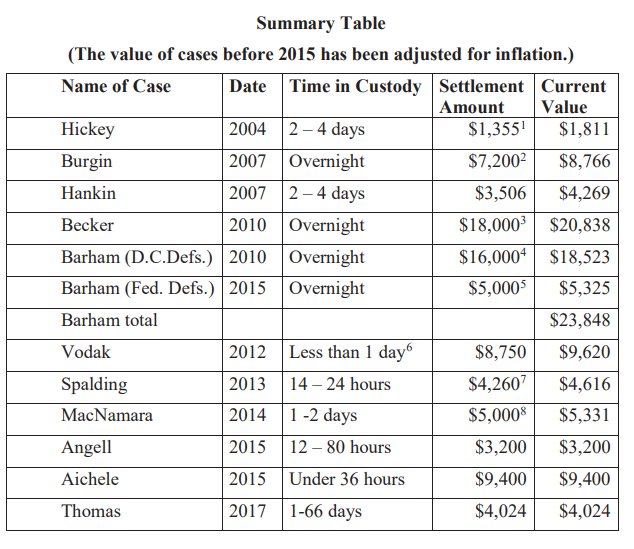

It seems that the way to make this argument in cases of police misconduct, false imprisonment, and so on, is to introduce an expert witness who has studied and/or been involved in many such cases. The plaintiffs also filed, therefore, a declaration by Michael Avery, who analyzes more than 20 cases of police misconduct involving wrongful imprisonment in which, at least in the class action ones, victims were paid between $1,800 and $23,000 as compensation for their loss of liberty. There is a transcription of this after the break, along with links to other interesting materials and a little background as well.

Note that the hearing on this motion is scheduled for January 14, 2019 at 8:30 a.m. in John Kronstadt’s courtroom in the First Street Federal Courthouse, which is 10B. Don’t be misled by the wrong date which appears on a bunch of these pleadings. It was an error, as reflected in this notice of error filed with the court a couple days ago.

You will, I have no doubt, recall that the basis of this case is, as the motion summarizes it:

… the unlawful detention and arrest of approximately 170 individuals engaged in demonstrations at or near the intersection of 6th and Hope Streets on November 26, 2014. The police herded Plaintiffs as they marched, finally trapping and surrounding them, preventing them from moving forward on the sidewalk. Plaintiffs allege that Defendants unlawfully kettled the demonstrators (preventing them from readily being able to disperse even if they could hear a dispersal order), and detained and arrested them without first issuing a lawful order to disperse (i.e., any order to disperse, to the extent one was given, was not audible to most people, and Defendants failed to ensure it was both heard and that members of the crowd knew what was expected of them). Plaintiffs also allege that Defendants unlawfully denied the class members release on their own recognizance (“OR release”) without an individual determination.

The motion argues in favor of money payments as compensation for this mistreatment, and in order to help the court determine the amounts, or to support their argument for how the trial should be conducted to help the jury determine the amounts, the plaintiffs also, as I said, filed this very interesting declaration of Michael Avery. The plaintiffs also filed a bunch of exhibits, which seem to be copies of the cases that Avery cites in his analysis. You can browse through them here on Archive.Org.

Declaration of Michael Avery:

Expert Witness Report of Michael Avery, Pursuant to FRCP 26 (a) (2)

I have been retained by Attorneys Barry Litt, Paul Hoffman, and Carol Sobel to give expert testimony in Chua v. City of Los Angeles, Case No. 2:16-cv-00237- JAK-GJS(x). The following is my report, pursuant to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

As set forth in greater detail in my Resume, attached as App. B, I have been admitted to the Bar since 1970. The majority of my law practice consisted of representing plaintiffs in civil rights claims in the trial courts, the Courts of Appeals, and the United States Supreme Court. The vast majority of these cases involved law enforcement misconduct. Since 1977 I have been a co-author of Police Misconduct: Law and Litigation, Avery, Rudovsky, Blum, & Laurin (West, current ed. 2017-2018, updated annually), which is generally considered the leading treatise in this field. In connection with annual updates the authors conduct a comprehensive review of relevant decisions from the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeals and add approximately 250 new cases to the book each year.

In 1998 I was one of the founders of the National Police Accountability Project (NPAP), a project of the National Lawyers Guild, and served as its President for a number of years. I have remained on the Board of Directors of NPAP over the life of its existence, and am currently a Vice-President. From 1998 to 2014 I was a professor at Suffolk University School of Law in Boston and now hold the rank of professor emeritus. As listed in my Resume, I have published several articles on the subject of police misconduct, in law reviews and elsewhere. Over the course of my career I have lectured and participated in panel discussions at dozens of CLE programs on the subject of civil rights law in general and police misconduct litigation in particular.

I. Statement of Opinions.

The history of class action litigation of cases similar to the instant case demonstrates that it is possible to arrive at figures for general damages for the loss of liberty in wrongful confinement cases. Lawyers for both plaintiffs and defendants have agreed that it is practical and fair to determine general damages for confinement. By “general damages” I mean compensation for the loss of freedom a person must endure when he or she is locked in jail. These damages are distinct from special damages that might be awarded for physical injuries, demonstrated emotional suffering, loss of wages, and the like. In the class actions described below, through negotiation and compromise, lawyers for plaintiffs and defendants have agreed on substantial awards for loss of liberty. Federal judges have approved the compensation in these cases as fair and reasonable. In total, millions of dollars have been awarded in this manner for wrongful compensation.

A number of factors influence the amount of compensation in any given case.

A settlement is a compromise in which plaintiffs accept compensation in a lower figure than they would hope to receive at trial. The amount of compromise may be influenced by the risk of losing at trial on the issue of liability and receiving no compensation, by the wish to avoid lengthy court proceedings which may extend for years, by the desire to avoid the stress, expense, and distraction of such proceedings, by the plaintiffs’ level of satisfaction with reforms obtained by the litigation through injunctive relief or otherwise, and many other factors. Where plaintiffs run the risks and endure the stress and expense of litigation by going to trial, most lawyers would expect them to receive substantially greater compensation than they would have obtained in a compromise settlement.

In some of the settlements below, the parties agreed to sub-classes to reflect different lengths of time in custody. For the most part, however, it was common for plaintiffs to agree to accept the same compensation for varying lengths of confinement measured in hours or a few days. This sort of “averaging” is a practical necessity in cases involving large numbers of people, although all would probably agree that it is a greater injury to be held for a longer period of time.

The settlements, expressed in current dollars, range from $1,811 (the oldest as well as the lowest case) to $23,848. The average settlement across the eleven class action cases was $8,702.

Collecting individual cases where general damages were awarded simply for loss of liberty was more difficult than finding class actions. Most individual cases include claims of physical injuries, significant emotional distress, loss of income, medical expenses, and similar elements of special damage. I have not reported individual cases where it appeared to me that elements of special damage might have predominated. I have included nine cases below where it appeared to me that the damages were awarded for loss of liberty, even though plaintiffs may have mentioned in their complaints factors that inevitably accompany incarceration, such as

humiliation, strip searches, and emotional distress short of trauma that requires treatment resulting in medical expenses. I have included these cases to demonstrate that where cases go to trial, or are settled for a single individual, damages may significantly exceed the settlement numbers in class action settlements.

II. Facts or Data Considered in Forming Opinions.

The facts I have taken into account in forming my opinions in this case include the general background obtained from my experience of police misconduct litigation over four decades, my scholarly research and writing, and my frequent contact with other lawyers who are experienced in civil rights litigation. Specifically, I have examined the records I have been able to gather regarding general damage awards for wrongful confinement. In the following paragraphs I summarize the cases I have taken into account. I gathered these cases by using the “Jury Verdicts and Settlements” feature of the Thomson Reuters Westlaw database. I supplemented that

by adding other cases that were known to me or to the plaintiffs’ lawyers through contacts in the civil rights community. Where possible, documents from the cases were obtained through PACER.

I have included all cases that I have been able to find where compensation was obtained in cases similar to the instant case, for the wrongful loss of liberty without consideration of testimony by an individual claimant with respect to physical injuries, emotional suffering, loss of income, or other elements of special damage. I have not excluded any case because the compensation fell outside of any range that I established either before or during the research. The court records or published reports on which I relied are attached in Appendix A. Where it was necessary to rely on the representation of counsel, that is noted in my description of the case.

Class Actions on Which My Opinion is Based

1. Hickey v. City of Seattle, No. COO-1672P (W.D. Wash. 2004)

Mass arrest of nearly 160 protestors at First Avenue and Broad Street, in Seattle, Washington. Protestors were incarcerated for between 40 hours and 4 days.

The case settled in 2004 for $250,000. Attorneys’ fees were to be not more than one-third of that sum ($83,333.33). Class representatives were to receive $2000 in addition to their per capita share of compensation. $162,666.67 was thus to be divided among the class members. 100% participation would have awarded each class member not less than $1000; 75% participation would have awarded each person approximately $1355. It is worth noting that in the Plaintiffs’ Motion for Final Approval of Class Settlement, under the heading of Likelihood of Success, the plaintiffs stated: Class counsel believe that while Plaintiffs presented a strong case against the City of violation of their Fourth Amendment rights, they had an uncertain likelihood of success on the only theory of liability they had remaining for trial—that a policymaker fore the city of Seattle ratified the decision to arrest the Class. While Class counsel cannot discuss the likelihood of success in detail, given that other Plaintiffs currently on appeal may litigate same or similar issues following any remand, it suffices to say here that the evidence on ratification was in dispute, and that there was a possibility that the Class could lose at trial.

In Hankin, below, liability was established in a trial before damages were settled.

2. Burgin v. District of Columbia, Civil Action No. 03-02005 (EGS) (U.S.D.C. D.C. 2007)

Mass arrest of between 158 and 190 protestors and others trapped within police lines, held overnight, restrained with flex cuffs attaching their wrist to ankle.

The case settled in 2007 for $1,000,000. Sixteen class representatives received $5000 each and attorneys’ fees and costs were $200,000. Plaintiffs’ counsel expected participation of 100 class members, which would have led to a recovery of $7,200 per person.

3. Hankin v. City of Seattle, 2007 WL 1566289, 2007 WL 2768885 (W.D. Wash. 2007)

Mass arrest of approximately 175 protestors at Westlake Park, in Seattle, Washington. Protestors were incarcerated for between 40 hours and 4 days.

After plaintiffs obtained a verdict on liability at trial, the case settled for $1,000,000. Four class representatives were awarded $2,500 each. Attorneys’ fees and costs were $450,000. There was a claims-retum rate of between 85% and 90%, resulting in 154 class members, who shared $540,000, for an award to each person of $3,506.49.

4. Becker v. District of Columbia, No. 01-CV-00811 (PLF) (JMF) (U.S.D.C. D.C. 2010)

Mass arrest, without prior warning or notice, of nearly 700 people for parading without a permit. Arrestees were held overnight and released the following day.

The case was settled in 2010 for a figure that would provide each class member who participated in the settlement with compensation of $18,000, assuming an expected participation rate of 75%. Class representatives received $50,000 each. Attorneys’ fees and costs were negotiated separately. 5. Barham v. District of Columbia, No. 02-CV-2283 (EGS) (JMF) (U.S.D.C.D.C. 2010, 2015)

Mass arrest of 400 individuals protestors and others trapped within police lines, held overnight (i.e., all were released in under 24 hours from time of arrest), restrained with flex cuffs attaching their wrist to ankle. This resulted in two class actions, one against the District of Columbia defendants and the other against federal defendants.

The District of Columbia case was settled in 2010 for a figure that would provide each class member who participated in the settlement with compensation of $18,000, assuming an expected participation rate of 75%. In fact the participation rate was higher and each person received approximately $16,000. Class representatives received $50,000 each. Attorneys’ fees and costs were negotiated separately.

The case against federal defendants was settled in 2015. The participation rate in the District of Columbia case had turned out to be higher than the expected 75%, and so plaintiffs’ counsel set the expected rate in the federal case at 85%. That would have resulted in 328 claimants, each of whom would have received an additional $5000, for a total recovery per person from both cases of approximately $21,000. Class representatives received no addition compensation beyond the per capita $5000 in the federal case. Attorneys fees and costs were negotiated separately.

6. Vodak v. City of Chicago, No. 03 C 2463 (N.D. Ill. 2012)

Several hundred protestors were arrested in downtown Chicago. Some were held for a period of time on the street and released, others were taken to police stations and detained and released without charges, and others were taken to police stations and detained, charged, and released only upon conditions of bond.

The case settled in 2012 for $6,200,000. Eleven class representatives received incentive awards in the amount of $7,750, and 37 class members who were deposed each received $1000. Class counsel received $14,000 to pay expert witness fees. Attorneys’ fees were negotiated separately. The settlement divided the remaining funds into three subclasses: (1) Persons who were arrested and detained from 90 minutes to three hours at the point of arrest (total of $100,000, $500 per person); (2) Persons who were arrested and detained at a police station, but released without being charged with any crime (total of $1,898,750, $8,750 per person); (3) Persons who were arrested and detained at a police station and charged with a criminal offense, released only upon conditions of bond, and required to appear in court on criminal charges which were ultimately dismissed in their favor (total of $4,065,000, $15,000 per person). Per person amounts were based on plaintiffs’ counsels’ estimates of the number of persons in each subclass.

7. Spalding v. City of Oakland. No. Cl 1-02867 THE (LB) (N.D. Calif. 2013)

Mass arrest of protestors, with no order or opportunity to disperse. Following a

two-hour detention on the street, the arrestees were left on buses with flex-tie handcuffs painfully holding their hands behind their backs and no access to toilets for two to six hours. Oakland deliberately refused to apply Pen. Code §853.6, holding the arrestees for 14 to 24 hours, before finally releasing them on citations for unlawful assembly. No formal charges were ever filed against any of them.

The case was settled in 2913 for $1,025,000. The four class representatives each received $9,000. Attorneys’ fees and costs of $350,000 were paid out of the settlement. The remaining $639,000 was to be equally divided among the 150 class members who submitted claims: $4260 each, if all class members made claims.

8. MacNamara v. City of New York, No. 04 Civ. 9216 (RJS (JCF) (S.D.N.Y. 2014)

Mass arrest of over 1000 protestors, at a number of different locations. Plaintiffs were held for between 24 and 48 hours, with some exceptions who were held longer, in a makeshift jail at Pier 57.

The case was settled in 2014. Twenty-four class representatives received compensation of $19,458.33. There was a separate award of attorneys’ fees. Class members who were detained received compensation in the amount of $5000. Those who were processed and charged only with violations received compensation of

9. Angell v. City of Oakland, No. C13-0190 NC (N.D. Calif. 2015) Mass arrest of 360 protestors, allegedly without a dispersal order. Plaintiffs claimed that while on the street and during transport they were painfully restrained in plastic handcuffs and not given access to toilet facilities, and held between 12 and 80 hours in severely overcrowded and unsanitary cells that were cold, lacked adequate seating, had no beds or bedding, and lacked telephones.

The case was settled for $1,360,000. Eight class representatives each received $9000 and the settlement allotted $350,000 for attorneys’ fees and costs. The remaining $938,000 was to be divided between all class members who filed claims forms. If all class members had made claims, they each would have received $2605.55. Atty. Yolanda Huang stated in a telephone call with Michael Avery that the papers on the case are in storage, but her best memory is that, given the number of claim forms returned, each person received approximately $3200.

In awarding preliminary approval to the settlement agreement, which was later given final approval by the court, the court noted: Class counsel asserts that, after evaluating the injuries received through this incident, plaintiffs unanimously agreed that the overriding harm was the corralling, arrest, and incarceration. Plaintiffs determined that while class members experienced a different length of time of incarceration, the amount of time was a secondary harm because everyone was held in similar conditions

10. Aichele v. City of Los Angeles, 2015 WL 4769568 (C.D. Calif. 2015)

Mass arrest of nearly 300 persons, including demonstrators, observers, and bystanders. Plaintiffs were held for varying lengths of time, up to 60 hours. Many were entitled to OR release, but were not promptly so released.

The case was settled for $2,675,000. Five named plaintiffs received $5000 as class representatives. The class administrator received $225,000. Attorneys’ fees were $668,750 and costs were $5,608.93. The court approved a cumulative point system for dividing the remaining funds among members of the class: four points for an arrest, four points for being a bystander (the vicinity subclass), two points for OR release in under 36 hours, and four more points for OR release above that. When a class member’s total points were computed, he or she fell into one of five groups to which compensation was awarded in the following amounts: $4,700, $7,000, $9,400, $11,700, $14,100.

The point set most accurately reflecting the Chua class is a non-bystander arrest with an OR release under 36 hours; such class members received six points and resulted in compensation of $9400 per class member.

11. Thomas v. Byrd, No. 2:25CV95BSM (E.D. Ark. 2017)

Holding arrestees in custody who could not afford to pay a debt to the City of Helena, Ark., for traffic tickets, minor offenses, or unpaid child support. The city would release the detainees once it became clear it could not obtain any payment from them. Twenty-one members of the class were held from between 1 to 66 days, according to an email from defense counsel. The court approved giving each member of the class the same amount of damages for reasons of notice and efficiency.

The case was settled for $210,000. Two class representatives received $15,000 and $6,000, respectively, and the court awarded $63,752.60 for attorneys’ fees and costs, to be paid from the settlement funds. Each member of the class received $4,040.24 in damages.

Note that there is also a series of individual, that is not class action, cases in Avery’s declaration. I’m leaving them out of this transcription here.

Image of Charmaine Chua is ©2018 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and is twisted around from this Twitter Pix right here.