The gallery owners also published and sold a book of selected images.1 Since then, though, the LAPD hadn’t let anyone else look at the pictures. Kim and Richard were lamenting the tragic fact that such important historical material had been cherry-picked by so few individuals, when there are many historians whose work would be enhanced by access – and by extension enhancing Angelenos’ understanding of our city.2

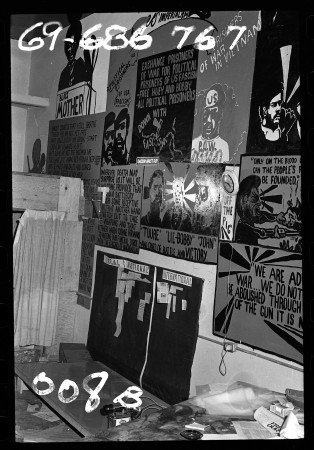

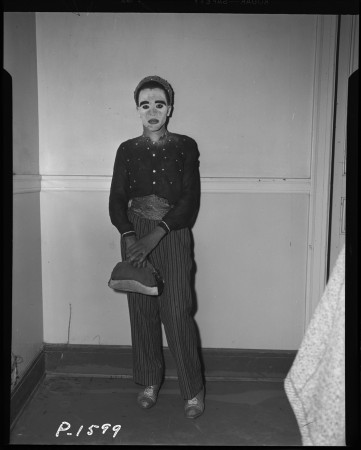

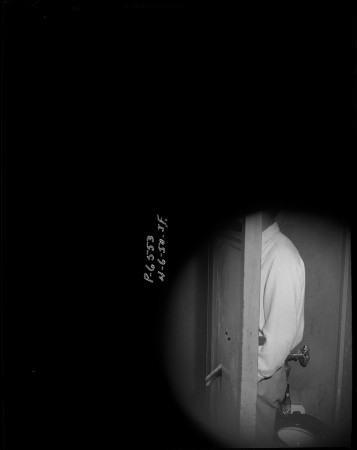

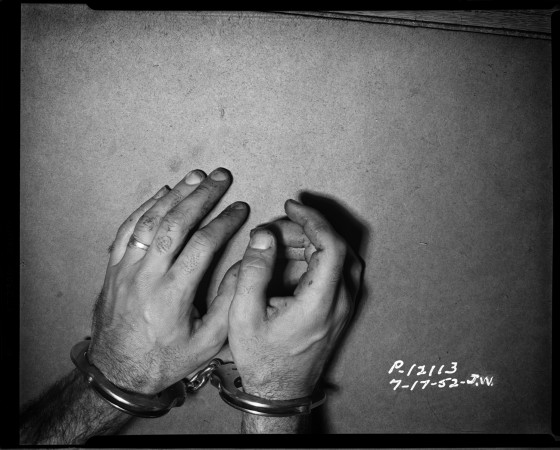

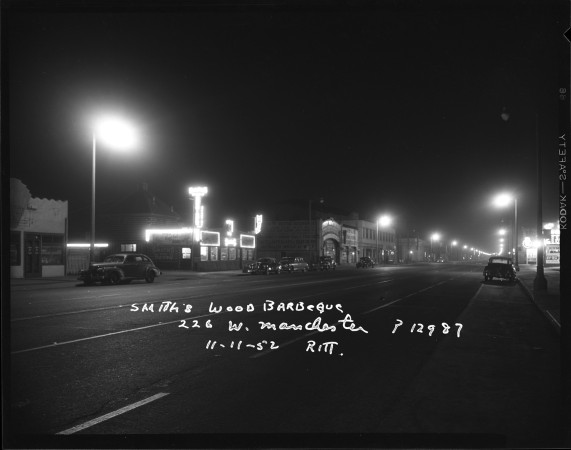

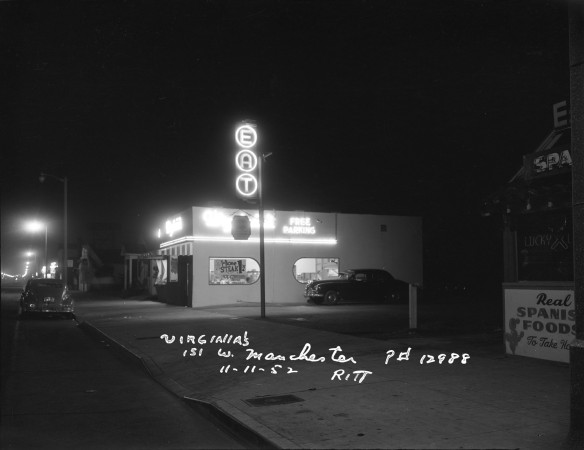

And that is really an understatement. Just look at the few examples scattered around this post, which I took from Fototeka’s site. There is an image from an LAPD men’s room spy camera, a picture of the Black Panther Party Headquarters after the shootout, a man apparently arrested for crossdressing, old buildings, many possibly unintentionally artistic closeups. An unimaginable variety.

These pictures could potentially give unprecedented insight into the LAPD’s past treatment of people of color, of LGBTQ people, gender noncomformists, and so on. Architecture, design, daily life. There is no limit to the public interest in seeing these images, in opening up this whole collection to the public. It is appalling that they’re not available to everyone.

Now, the California Public Records Act is very, very clear that photographs are public records.3 And it’s also very clear that once a public record has been released to one member of the public it can no longer be withheld from any member of the public.4 Clearly, then, I thought, we are going to get access to these photos! So I submitted a request through the City’s NextRequest platform.

Now, the LAPD is famous for its idiotic denials, and their first response was consistent with their reputation. They told me that I couldn’t have them because they are investigative materials and therefore exempt under §6254(f).5 So I told them about the fact that a release to anyone constitutes a waiver and asked them to change their mind.

They ignored me, as they are wont to do, so I wrote to the City Attorney and asked again. And they also ignored me. So I contacted the incomparable attorney Anna von Herrmann and asked her what she thought. And what she thought was that we should file a petition to force the City to release the photos. And that’s what we did, and here is a copy for you! Read on for some selections.

1. This is a petition to enforce the California Public Records Act (“CPRA”) against Respondent and Defendant (“Respondent”) the City of Los Angeles (“the City”). Petitioner and Plaintiff (“Petitioner”) [Mike Kohlhaas] , a local professor and open-records activist, submitted a request to Respondent for historical Los Angeles Police Department (“LAPD”) photographs held in the City Archives. The records Petitioner requested are easy to identify and subject to mandatory disclosure under the CPRA. Indeed, the City previously allowed other members of the public to inspect and copy these exact photographs in order for those parties to exhibit the photos in a private art gallery, display them in a book published for profit, and charge hundreds of dollars for individual prints of the photos. By so doing, the City waived any possible exemptions to disclosure that may arguably have applied to these photographs. Nevertheless, the City has flatly refused to allow Petitioner to access these public records. Respondent has thereby violated the CPRA and the California Constitution.

2. The LAPD archive photographs at issue in this case are of immense historical and educational value. By only selectively allowing their release, the City has predicated the public’s access to these photos on the ability to pay a private party for the privilege of viewing them. Scholarly and educational access to this historical information is frustrated by the City’s flagrant violation of the CPRA. By this Petition and Complaint (“Petition”) and pursuant to the Code of Civil Procedure §§ 1060 and 1085, Civil Code § 3422, and Government Code §§ 6250, et seq., Petitioner respectfully requests from this Court (1) a writ of mandate to command Respondent to disclose all non-exempt information Petitioner requested and thereby comply with the CPRA; (2) a declaration that Respondent’s withholding of these public records violates the CPRA; and (3) a permanent injunction enjoining Respondent from continuing its pattern and practice of denying access to public records in violation of the CPRA.

7. Petitioner is informed and believes, and on that basis alleges, that the City previously disclosed all the LAPD photographs in its archives to at least three members of the public.

8. In 2001, Merrick Morton (a photographer and co-owner of a private gallery called Fototeka), Robin Blackman (co-owner of Fototeka), and Tim B. Wride (associate curator of photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art) requested access to LAPD’s photo archive. The three desired to access the photos so they could display some of them at an exhibition they were planning for their private gallery.

9. Petitioner is informed and believes, and on that basis alleges, that the City previously The City granted this request. Mr. Morton, Ms. Blackman, and Mr. Wride were all given full access to LAPD’s photo archives. The City also permitted them to make copies of the photos.

10. These three individuals displayed the LAPD photos at a Fototeka exhibition titled “To Protect and Serve: The LAPD Archives.” Mr. Morton and Ms. Blackman created and organized the exhibition, and Mr. Wride served as co-curator. Since its debut at Fototeka in 2001, the LAPD Archives exhibition has had at least eight other showings around the world; its most recent showing took place in the summer of 2019.

11. Fototeka continues to sell prints from the LAPD Archive collection. They charge between $450 and $950 for individual prints of these photos.

12. In 2004, many of the LAPD photos were also published in a book titled “Scene Of the Crime – Photographs from the LAPD Archive.” Mr. Wride, as well as author James Ellroy, were involved in the book’s publication.

34. Petitioner submitted a request for easily identifiable public records that the City previously disclosed to other members of the public. Respondent denied Petitioner all access to these records, thereby violating the CPRA.

35. Petitioner maintains that many of the photographs contained in the LAPD archives are not investigatory records exempt from disclosure under § 6254(f) as the City claims. However, even assuming, arguendo, that all these photographs could be considered exempt under § 6254(f), the City has clearly waived that exemption by disclosing those records to other members of the public. § 6254.5.

36. Section 6254.5 states that if a public agency “discloses a public record that is otherwise exempt . . . to a member of the public, this disclosure shall constitute a waiver of the exemptions . . .” The statute’s legislative history shows that the provision was intended to codify the holding in Black Panther Party v. Kehoe, 42 Cal.App.3d 645 (1974) (“Kehoe”), that selective disclosure and withholding is not permissible under the CPRA. See Newark Unified School Dist. v. Superior Court, 245 Cal.App.4th 887, 902 (2015) (“Newark”) (“[Kehoe] is the ruling section 6254.5 was intended to codify.”).

37. In Kehoe, the plaintiffs filed CPRA requests with the state agency in charge of licensing debt collection businesses, seeking copies of citizen complaints regarding those businesses. The agency regularly disclosed the complaints to the businesses themselves; however, just as in the present case, the agency in Kehoe refused to allow plaintiffs to access the complaints, arguing that they were investigatory records exempt from disclosure under § 6254(f). Although the Court of Appeal agreed that the complaints did fall under § 6254(f), the Court still ordered that the agency disclose the documents to plaintiffs because it found that the agency waived the exemption when it released the complaints to the businesses. The Court explained:

[P]ublic officials may not favor one citizen with disclosures denied to another. . . .[R]ecords are completely public or completely confidential. The [CPRA] denies public officials any power to pick and choose the recipients of disclosure. When defendants elect to supply copies of complaints to collection agencies, the complaints become public records available for public inspection.39. Here, the City clearly allowed other members of the public to access the photos in the LAPD archives. In so doing, the City waived any exemptions that may have otherwise applied to the photos, including the investigatory records exemption at § 6254(f). Nevertheless, the City has refused to allow Petitioner to benefit from the same access to these public records. By unlawfully opting for “selective disclosure” and continuing to withhold these photographs from Petitioner, the City has plainly violated the CPRA.

40. Respondent’s refusal to disclose these records to Petitioner not only violates the letter of the CPRA, but also its spirit. The effect of the City’s selective disclosure is to allow private gallery owners to utilize these public records for profit, but to deny all access to other members of the public. As such, in order to inspect these public records, members of the public must either attend an exhibition at a private gallery, purchase a privately published book, or pay a minimum of $450 per photo to a private actor. The City’s actions have taken public records with immense historical and scholarly value and predicated the public’s access to them on the ability to pay top dollar to a private entity. This favoritism will persist absent judicial intervention.

- With a foreword by James Freaking Ellroy, no less. Selected photos from the collection also appeared in L.A. 53, with prose by, as the L.A. Times put it in their review, “the bombastic James Ellroy.”

- Which is how Kim explained it to me!

- The definition, found at §6252(g), includes:

any handwriting, typewriting, printing, photostating, photographing, photocopying, transmitting by electronic mail or facsimile, and every other means of recording upon any tangible thing any form of communication or representation, including letters, words, pictures, sounds, or symbols, or combinations thereof, and any record thereby created, regardless of the manner in which the record has been stored.

- At §6254.5, which states:

Notwithstanding any other law, if a state or local agency discloses a public record that is otherwise exempt from this chapter, to a member of the public, this disclosure shall constitute a waiver of the exemptions specified in Section 6254 or 6254.7, or other similar provisions of law.

- Which exempts Records of complaints to, or investigations conducted by, or records of intelligence information or security procedures of, the office of the Attorney General and the Department of Justice, the Office of Emergency Services and any state or local police agency, or any investigatory or security files compiled by any other state or local police agency.

This is fascinating. I have been researching some crimes from 1929 and has the impression no LAPD photos existed from then. I am now rethinking that!