After a bunch of incredibly vigorous argument at the hearing last month, for which Judge Mitchell Beckloff did not prepare a written tentative ruling, he has issued his final ruling. Get a copy of it here, and other pleadings in the case here. Read on for transcribed selections, which I am not commenting on at all until every part of the case is resolved, because I’m not really competent to do so, but I wanted to publish this because it’s important, at least to me.

After a bunch of incredibly vigorous argument at the hearing last month, for which Judge Mitchell Beckloff did not prepare a written tentative ruling, he has issued his final ruling. Get a copy of it here, and other pleadings in the case here. Read on for transcribed selections, which I am not commenting on at all until every part of the case is resolved, because I’m not really competent to do so, but I wanted to publish this because it’s important, at least to me.

ORDER DENYING IN PART AND GRANTING IN PART PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDATE

Petitioner [Mike] seeks a writ of mandate under Code of Civil Procedure section 1085,

subdivision (a) and the California Public Records Act (CPRA) (Government Code sections 6250 et seq.) ordering Respondent Downtown Los Angeles Property Owners Association, also known as the Fashion District Business Improvement District (Respondent or BID), to produce documents concerning three separate CPRA requests.

The Petition is DENIED in part and GRANTED in part.

[The BID objected to my introduction of responsive emails obtained from other BIDs on the grounds that they were hearsay]

Respondent’s other grounds stated for the objections are and were overruled. [The emails are relevant as Petitioner is using the emails to demonstrate documents responsive to his CPRA request exist and were not produced. The hearsay objection is not well taken because the emails are being used to show they exist, not for the truth of what is stated in them. Whether the emails are true does not matter to Petitioner’s position that emails were not provided pursuant to his CPRA request. Lack of personal knowledge and foundation are similar to the hearsay objection. Any characterization of the content of the emails would lack foundation as the emails were not from or to Petitioner. The content of the emails does not matter, however, to Petitioner’s claim—only the existence of the emails matters to his position in this litigation.

After considering Petitioner’s argument, however, the court finds the emails (Exhibit A) are sufficiently authenticated and overrules the objections to the exhibits. Petitioner attested he received the emails from other business improvement districts after he made CPRA requests. His testimony as to each email is specific—”I received this email on November 23, 2018, in response to a CPRA request to the Melrose BID.” ([Mike] Deck, H 5. See also [Mike] Deck HH 5-7.) Such testimony is “evidence sufficient to sustain a finding that [the writing] is the writing that the proponent of the evidence claims it is.” (Evid. Code § 1400. See also Law Rev. Com. Comment to Evid. Code § 1400.)

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

CPRA Request No. 1:

On May 17, 2017, Petitioner submitted a CPRA request (Request No. 1) to Respondent. This request sought three categories of emails; two are at issue in this action. First, Category 1 sought all emails between anyone at the BID, staff or Board, and the South Park BID or the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council from January 1, 2016 through May 15, 2017. (Pet., H 10.) Category 2 sought all emails from 2017 in the possession of Mark Chatoff, the Chairman of the BID’s Board of Directors, relating to the operation of the BID. (Pet., H 10.)

On July 14, Respondent provided a substantive response containing 46 emails which the BID described as “the ‘completed response.’ ” (Pet., 11-12; see [Mike] Deck, H 2.)

Petitioner indicated to the BID he believed the response was deficient as the production contained no emails from Board Members in response to Category 1, and the production did not contain a single email from Chatoff in response to Category 2.

In attempting to determine why certain documents were apparently withheld, Petitioner requested an explanation from Respondent. In response, Respondent claimed that “all non¬ exempt records have been submitted,” that “any exemptions are due to deliberative process,” and that “the BID has no records responsive” to Category 2. (Pet., H 12.)

CPRA Request No. 2:

On July 7, 2017, Petitioner submitted a CPRA request (Request No. 2) to Respondent for “all emails between anyone at [Urban Place Consulting] and anyone at the BID (staff and Board) exclusive of [BID Executive Director Rena Leddy] from January 1, 2017 through whenever [Respondent] complies] with this request.” (Pet., H 17.)

On July 17, 2017, Respondent responded by indicating that “some records … are exempt from disclosure as deliberative process” and estimating that it would provide all non-exempt records and information “within the next two weeks.” (Pet., H 19.) Petitioner did not receive a response until October 13, 2017. (Pet., H 21.) The response indicated certain records were exempt under the deliberative process and that the Respondent did not have responsive records. (Pet., H 21.)

CPRA Request No. 3:

On July 31, 2017, Petitioner submitted a request (Request No. 3) for copies of all 2017 emails in the possession of Linda Becker. 1 2

When, on August 18, Petitioner inquired as to the status of the request, the BID responded there were no responsive records and it was not claiming any exemptions. (Pet., H 24.) Thereafter, Petitioner informed Respondent that responsive documents must exist because Respondent emailed the Board Members in early August regarding an upcoming meeting. (Pet., H 25.) Respondent then asserted that the records sought in CPRA Request No. 3 are “exempt from disclosure pursuant to the deliberative process privilege” but agreed to produce the email identified by Petitioner. (Pet., U 25.)

Petitioner contends, to date, Respondent failed to produce a single email from Becker in response to this request, including the email advising Becker of the Board Meeting. ([Mike] Deck, H 12.)

STANDARD OF REVIEW

Petitioner takes the position Respondent has violated both the procedural and substantive requirements of the CPRA by withholding records, improperly invoking the deliberative process privilege, and refusing to search for records. (OB, p. 5:8-16.)

Code of Civil Procedure section 1085, subdivision (a) provides in relevant part:

“A writ of mandate may be issued by any court to any inferior tribunal, corporation, board, or person, to compel the performance of an act which the law specially enjoins, as a duty resulting from an office, trust, or station, or to compel the admission of a party to the use and enjoyment of a right or office to which the party is entitled, and from which the party is unlawfully precluded by that inferior tribunal, corporation, board, or person.”

“There are two essential requirements to the issuance of a traditional writ of mandate: (1) a clear, present and usually ministerial duty on the part of the respondent, and (2) a clear, present and beneficial right on the part of the petitioner to the performance of that duty. (California Ass’n for Health Services at Home v. Department of Health Services (2007) 148 Cal.App.4th 696, 704.) “Generally, a writ will lie when there is no plain, speedy, and adequate alternative remedy-” (Pomona Police Officers’ Ass’n v. City of Pomona, (1997) 58 Cal.App.4th 578, 583-84.)

“When there is review of an administrative decision pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 1085, courts apply the following standard of review: ‘[Judicial review is limited to an examination of the proceedings before the [agency] to determine whether [its] action has been arbitrary, capricious, or entirely lacking in evidentiary support, or whether [it] has failed to follow the procedure and give the notices required by law.’ [Citations.]” (Pomona Police Officers’ Ass’n, supra, 58 Cal.App.4th at 584)

Pursuant to the CPRA, individual citizens have a right to access government records. In enacting the CPRA, the California Legislature declared that “access to information concerning the conduct of the people’s business is a fundamental and necessary right of every person in this state.” (Gov. Code, § 6250; see also County of Los Angeles v. Superior Court (2012) 211 Cal.App.4th 57, 63.) Gov. Code § 6253, subdivision (b) states:

“Except with respect to public records exempt from disclosure by express provisions of law, each state or local agency, upon a request for a copy of records that reasonably describes an identifiable record or records, shall make the records promptly available to any person upon payment of fees covering direct costs of duplication, or a statutory fee if applicable. Upon request, an exact copy shall be provided unless impracticable to do so.” (Gov. Code § 6253, subd. (b).)

ANALYSIS

The oral argument on the petition was extensive. The court provided an oral tentative decision, both parties argued, and there was considerable discussion with the court on various points.

Petitioner requests the court declare Respondent must comply with the CPRA’s procedural requirements, declare that Board Member emails are subject to the CPRA and must be produced, and issue a writ of mandate directing Respondent to conduct a reasonable search for records and to provide all responsive non-exempt records.

Government Code section 6253, subdivision (c) provides that “upon receiving a request for a copy of public records, [each agency] shall, within 10 days determine whether the request seeks public records in the possession of the agency that are subject to disclosure. If the agency determines that the requested records are not subject to disclosure,… the agency promptly must notify the person making the request and provide the reasons for its determination.” (Filarsky v. Superior Court (2002) 28 Cal.4th 419, 426.)

To establish an agency has a duty to disclose under Government Code section 6253, subdivision (c), the petitioner must show that: (1) the record “qualifies] as [a] ‘public record[ ]’ ” within the meaning of section 6252, subdivision (e); and (2) the record is “in the possession of the agency.” (Consolidated Irrigation Dist. v. Superior Court (2012) 205 Cal.App.4th 697, 708.)

Request No. 1, Category 1:

All emails between anyone at the BID, staff or Board, and the South Park BID or the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council from January 1, 2016 through May 15, 2017

Leddy offered her sworn testimony that Respondent produced all responsive records to Petitioner’s May 17, 2017 CPRA request. 3 (Leddy Deck, H 20:26-27.) Leddy also attested Respondent has adopted a policy allowing employees to delete certain emails—those “which do not contain content that is necessary for [the employee] to do [his/her] job effectively (Leddy Decl., H 19:28-1.) Some employees “are more consistent in deleting emails than others.” (Leddy Decl., H 19:3-4.) The email retention policy was based on Respondent’s information technology consultant advising Leddy that deleting emails stored on Respondent’s computers would “decrease its email storage costs and Outlook would work faster if emails were deleted.” (Leddy Deck, H 19:26-27; see also Fernandez Deck, H 5.)

As argued by Petitioner, Riskin’s Exhibit A demonstrates there appears to have been some communication by email responsive to Request No. 1 that were not produced by Respondent to Petitioner. Leddy’s declaration does not specifically explain why emails produced by another business improvement district were not produced by Respondent.

As noted during the hearing, context here is important to credibility.

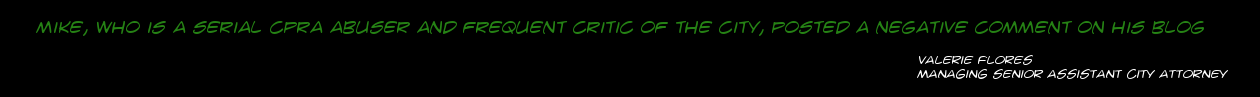

Respondent is not required under its contract with the City to retain general emails in the course of its operations. 4 (Leddy Deck, Exhibit 2, Section 7.) Respondent allows emails that are not required for an employee to do his/her job effectively to be deleted. Respondent began actively deleting emails in 2015. (Fernandez Deck, H 5.) Petitioner has made 78 CPRA requests of Respondent “with multiple Subparts, and multiple Subparts of Subparts.” 5 (Leddy Deck, H 18.) Respondent has also responded to Petitioner’s requests under the Brown Act. (Leddy Deck, H 18.) To date, Respondent has produced more than 5,000 pages to Petitioner. (Leddy Deck, H 18.) Leddy has interacted with Petitioner concerning his requests over the last four years.

(Leddy Deck, H 28.) Respondent’s Board members are all volunteers. (Leddy Deck, H 6.)

Leddy attested Respondent produced all responsive records to this request and did not withhold any documents based on any exemptions. All Board members also attested they had no documents as of May 17, 2017 responsive to the CPRA request. The Board members also

for emails, every BID employee, both administrative and in the field, must search their own emails for the records sought.” (Leddy Deck, H 19.) Leddy then reviews all emails identified by the seven employees “to determine whether exemptions apply, and what if any redactions are appropriate.” (Leddy Deck, H 19.) Knowing Respondent’s obligations under the CPRA, for Leddy to declare under penalty of perjury Respondent produced all responsive records, Respondent must have followed its usual and customary process in responding to Petitioners’ CPRA requests.

Given the nature/content of the emails produced by another business improvement district, Respondent’s sworn statement that it produced all responsive documents and given the context set forth above, the court finds Leddy’s statement Respondent produced all responsive documents credible. That the emails attached as Exhibit A to Riskin’s declaration were not produced does not undermine Leddy’s testimony given the nature of those emails and Respondent’s email retention policy initiated in 2015—a statement Respondent would not sponsor a Women & Safety Fireside chat, a comment about a survey to be distributed (apparently) concerning business improvement district salaries and benefits, a June 2016 consortium meeting reminder and agenda (distributed to approximately 50 individuals), and a February 2017 consortium happy hour in Flollywood (distributed to approximately 50 individuals).

For the same reasons, the court finds the Board members’ declarations credible.

Request No. 1, Category 2:

All emails from 2017 in the possession of Mark Chatoff the Chairman of the BID’s Board of Directors, relating to the operation of the BID

Again, Respondent swore it had no documents in its possession responsive to this specific request. For those reasons stated above, the court finds Respondent’s position credible.

In addition, Chatoff attested in his sworn statement submitted in opposition to the petition: “As of May 17, 2017 [the date of the CPRA request], I did not have any email communications to or from southpark.la, dlanc.com, delsonproperties.com, South Park BID, DLANC, Delson, or Michael Delijani, in my private email that pertained to my role as a BID Board Member. I did not delete emails because of any CPRA request.” (Chatoff Deck, H 5.) He further attested he does not keep emails unless he needs them for future use. (Chatoff Deck, H 7.) Chatoff attested emails from Respondent’s staff remain in his private email “only long enough for [him] to read it, and/or print_” (Chatoff Deck, H 10.)

Again, given the context set forth above, and Chatoff s sworn statement, the court finds Respondent and Chatoff complied with their obligations under the CPRA.

[While the court sustained the objection to Exhibit F of the Petition, even if the court had not done so, Chatoff provided two reasons the email was not provided. First, Chatoff explained the Skidrow Neighborhood Council concerned him as a business owner given the location of his property. Second, on May 17, 2017, he no longer had the email in his possession. (Chatoff Deck,Request No. 2:

All emails between anyone at [Urban Place Consulting] and anyone at the BID (staff and Board) exclusive of [Leddy] from January 1, 2017 through whenever [Respondent] complies] with this request

As a preliminary matter, Petitioner takes issue with Respondent limiting its search to the date of a request, rather than the date of the search. (Reply 10:6-7.) Petitioner argues given the CPRA’s intent and purpose in favor of disclosure, Respondent’s decision to exclude records created or obtained after the date of the CPRA request is improper.

There is no clear legal authority on the issue. Nonetheless, the court finds that, for practical reasons, the universe of documents responsive to a CPRA request should be constrained by the date of the CPRA request—not the date of the documents are produced.

The reason for this is simple: A document search may take several days to conduct and may also require review by multiple employees. An end date for the document search based on the production date creates uncertainty as to the producing entity’s obligations and the scope of the document production; in other words, it would create a constantly shifting target of documents especially where, as here, an organization requires one person to review responsive documents for exemptions. Unlike the static date of the request itself, requiring an entity to produce documents based the date of its production may inadvertently require a party to constantly search and re-search for documents when a document review extends for multiple days. Moreover, there is no prejudice to the requestor by applying the date of the CPRA request because a requestor can always submit another request for a different time period if necessary.

As to Respondent’s response to Request No. 2, there is no dispute Respondent withheld certain documents based on the “deliberative process privilege.”

“The right of access to public records under the CPRA is not absolute.” (Copley Press, Inc. v. Superior Court (2006) 39 Cal.4th 1272, 1283.) The CPRA makes clear that “every person” has a right to inspect any public record (Gov. Code § 6253, subd. (a)), for any purpose (Id. at § 6257.5), subject to certain exemptions, including those found in Government Code section 6255. Government Code section 6255 exempts from disclosure documents which are protected by the deliberative process privilege. (Wilson v. Superior Court (1996) 51 Cal.App.4th 1136,1142.)

“[I]t is the public agency’s burden to prove a basis for nondisclosure of a public record.” (Sander v. Superior Court (2018) 26 Cal.App.5th 651, 670.)

“Under the deliberative process privilege, senior officials of all three branches of government enjoy a qualified, limited privilege not to disclose or to be examined concerning not only the mental processes by which a given decision was reached, but the substance of conversations, discussions, debates, deliberations and like materials reflecting advice, opinions, and recommendations by which government policy is processed and formulated.” (Citizens for Open Government v. City of Lodi (2012) 205 Cal.App.4th 296, 305; Caldecott v. Superior Court (2015) 243 Cal.App.4th 212, 225.)

Importantly, “[njot every disclosure which hampers the deliberative process implicates the deliberative process privilege. Only if the public interest in nondisclosure clearly outweighs the public interest in disclosure does the deliberative process privilege spring into existence.

The burden is on the [one claiming the privilege] to establish the conditions for creation of the privilege.” (California First Amendment Coalition v. Superior Court (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 159, 172-173; Citizens for Open Government v. City of Lodi, supra, 205 Cal.App.4th at 306.)

In support of its claim for exemption, Respondent submits the declaration of Jose Gonzalez, Finance Manager for Respondent. Gonzalez attests that he searched the “emails to or from Urban Place Consulting Group Inc., excluding Ms. Leddy’s emails to or from Urban Place Consulting Group Inc., in response to [Mike]‘s July 7, 2017, CPRA request_” (Gonzalez Deck, D 4.) Gonzalez represents the emails he “located constituted deliberative process. In particular, Urban Place Consulting Group Inc. and [Gonzalez] were assisting Ms. Leddy in evaluating various special assessment methodologies for the renewal of the BID contract with the City of Los Angeles.” (Gonzalez Deck, H 4.) According to Gonzalez, “Ms. Leddy ultimately made a policy recommendation to the BID Board, which was accepted, and the final special assessment methodology is described and explained in the Management Plan. (Gonzalez Deck, D 4, Ex. 4 [Management Plan].) Gonzalez states “[t]hese emails had nothing to do with illegal lobbying.” (Gonzalez Deck, H 4.)

As requested by Petitioner, the court examined in camera the records withheld by Respondent responsive to this request on the basis of deliberative process privilege. (Gonzalez Deck, H 3, Exhibit 10; Humiston Deck, H 3.) Having reviewed the records, the court finds Respondent’s assertion of the exemption is not wholly justified. The court finds certain portions of the emails withheld (Exhibit 10) may be redacted and the information withheld under the deliberative process privilege while other portions may not. (Gov. Code § 6253 ; subd. (a).)

Exhibit 10 consists of five pages total. Within the five pages, there are two email strings. One email string is two pages while the other is three. In the first two pages (one email string):

The first email (meaning the last message in the string) is dated January 23, 2017 at 10:07:44 a.m. There is nothing the email that is privileged, and the entire text for this particular email shall be disclosed.

The next or second email is dated January 23, 2017 at 9:39 a.m. The second (and final) sentence of the second paragraph is properly redacted pursuant to the deliberative process privilege. The remaining portions of this particular email shall be disclosed.

The third email in the string is dated January 20, 2017 at 1:02 p.m. The last sentence in this particular message is properly redacted pursuant to the deliberative process privilege. (It is the sentence immediately preceding “thanks, [Name]”.) The remaining portions of this particular email shall be disclosed.

The fourth and final email in this string is dated January 20, 2017 12:56 p.m. Nothing in this particular message is properly withheld pursuant to the deliberate process privilege, and this particular message shall be disclosed in its entirety.

In the three remaining pages (second email string):

The first email is dated February 27, 2017 at 6:44 p.m. The first and third sentences of the message were properly withheld as exempt under the deliberative process privilege. The second (and middle) sentence of this particular email shall be disclosed.

The second email is dated February 27, 2017 at 6:30 p.m. The third sentence (a question) was properly withheld pursuant to the deliberative process privilege. The balance of this particular email shall be disclosed.

The third email is dated February 27, 2017 at 6:26 p.m. The last two sentences of this particular email were properly withheld pursuant to the deliberative process privilege. The balance of this particular email shall be disclosed.

The fourth email is dated February 27, 2017 at 6:14 p.m. The entirety of this particular email message was properly withheld pursuant to the deliberative process privilege except for the second sentence (a question) in the second paragraph. The second sentence (a question) in the second paragraph of this particular email shall be disclosed.

The fifth email is dated February 27, 2017 at 5:38 p.m. The two-word salutation and the three-word conclusion shall be disclosed. The three paragraphs constituting the body of this particular email were properly withheld pursuant to the deliberative process privilege.

The sixth email is dated February 27, 2017 at 1:30 p.m. The first paragraph is one sentence long. The last six words of this sentence were properly withheld pursuant to the deliberative process privilege. The second paragraph was also properly withheld pursuant to the deliberative process privilege. The balance of this particular email shall be disclosed.

In addition, as discussed during the hearing, the court cannot find on this evidence Respondent undertook an adequate and reasonable search for documents responsive to this request. Despite having seven employees, it appears Respondent required only one employee to conduct a search for documents responsive to this CPRA request. (Leddy’s emails were not included in this request.) Leddy provides no explanation for how searching only one of Respondent’s employee’s computers was a reasonable search. (Leddy Deck, H 21.) Asking only one employee to search is inconsistent with Leddy’s statement “whenever” she provides a CPRA response, all employees are required to search their computers. (Leddy Deck, H 19.)

Moreover, Exhibit 18 of Leddy’s declaration at page 301 suggests Respondent undertook no real search. On August 18, 2017 at 3:00 p.m., after being prodded by Petitioner, Leddy wrote to Gonzalez and inquired, “Do you have any emails [from] UPC that are not specific to renewal or in ‘draft form’? I imagine the only items we have to deliver are meeting notices or arrangements.” Only 38 minutes later, Gonzalez responded, “I believe all my emails would be exempt from disclosure as being part of the deliberative process. I never send meeting notices for renewal meetings.”

While Respondent’s counsel suggests Leddy’s failure to make a showing of a reasonable and adequate search was a declaration drafting error, the court did not permit Leddy to submit a supplemental declaration to address the issue as it would have been fundamentally unfair to Petitioner. Petitioner would have had no real opportunity to respond to any new evidence submitted after the hearing.

Accordingly, the court orders Respondent to undertake an adequate and reasonable search for documents responsive to Request No. 2. Any documents discovered after an adequate and reasonable search shall be provided with the documents from Exhibit 10 in redacted form.

Request No. 3:

Copies of oil 2017 emails in the possession of Linda Becker that relate to the operation of the BID

Like the other Board members, Becker attested she had no emails responsive to Request No. 1 or Request No. 2. For reasons discussed earlier, the court finds Becker credible. Becker also stated in her declaration as of July 31, 2017 (the date of Petitioner’s CPRA request), she had only one email in her possession (Exhibit 9) somewhat related to the request. (Becker Deck, H 9.) Becker disputed, however, that the email was responsive because it did not relate to the operation of Respondent. (Becker Deck, H 9.)

The court reviewed Exhibit 9 in camera. The court finds the email is not responsive as it does not relate to the operation of Respondent.

Declaratory Relief:

Petitioner requests in his Reply Brief—not in his Opening Brief or Petition—“declaratory relief as to the disclosability of Board Members’ emails, as to the BID’s obligations to search for records and respond to requestors under § 6253(c), and as to the standard when a record relates to the ‘conduct of the people’s business’ under § 6252(e).” (Reply 1:21-24.) As the request exceeds the scope of the Petition, the request for a declaration on those issues is denied. Moreover, as the court did not reach the issues in resolving the Petition, such a declaration would operate as an advisory opinion.

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, the petition is DENIED in part and GRANTED in part. Petitioner shall prepare an order and judgment consistent with this decision.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Dated: July 1 2019

Hon. Mitchell Beckloff

Judge of the Superior Court