Last week USC hosted a celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti was invited to speak, but his speech was repeatedly interrupted by protesters from LA CAN, from the Skid Row Neighborhood Council Formation Committee, from NOlympics LA, and others.

Last week USC hosted a celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti was invited to speak, but his speech was repeatedly interrupted by protesters from LA CAN, from the Skid Row Neighborhood Council Formation Committee, from NOlympics LA, and others.

This prompted an editorial from the L.A. Times entitled Shouting down Mayor Garcetti isn’t ‘speaking truth to power,’ the theme of which is well summarized by this excerpt:

But protesters can overplay their hands. These days, tolerance of other people’s views seems low, and there’s an unhealthy willingness to silence one’s opponents rather than engage them, debate them and out-argue them. That’s a shame.

Protesters who shout down a speaker — or shut down a public meeting — aren’t just expressing their own views; they’re making it impossible for others to share theirs.

It’s silly almost beyond comprehension to believe that Eric Garcetti can be silenced by protesters, that anyone interrupting him can make it impossible for him to share his views. Every word the man says is reported on extensively. His press releases are reprinted or recited verbatim by major news outlets. His press conferences are attended by reporters from all over the state, even the nation. A few people interrupting a speech isn’t making it impossible for Eric Garcetti to share his views.

And why in the world does the Times think there’s something wrong with protesters being unwilling to debate or out-argue Eric Garcetti? Do they really believe that if Eric Garcetti just hears the right argument he’ll stop allowing his LAPD thugs to kill young men for no good reason, stop sending them out to arrest homeless people and incinerate their belongings, that he’ll stop accepting campaign money from real estate developers in exchange for enabling them to destroy neighborhoods and cause more homelessness, that he’ll suddenly see the light and stop being evil?

It’s not going to happen like that. He’s heard the arguments already. If he hasn’t seen the damage he’s doing, the pain he’s causing, the killings he enables, all for the sake of his campaign coffers and his career, it’s because he doesn’t want to see. He knows his constituency and he’s giving them exactly what they want from him. No reasoned analysis is going to change that. These kind of repeated demands for civil discourse in the face of racist police murders, genocidal policies on homelessness, gentrification by force of arms, are incredibly disingenuous.

And strangely, it doesn’t seem to have occurred to the LA Times that the protesters already know they’re not going to change Eric Garcetti’s mind about anything. These protesters are accomplished, able, serious people, the value of whose contributions to civil society in Los Angeles is incomparable. None of them have done what they’ve been able to do by wasting their time trying to debate LA politicians into being nice. What, the LA Times pointedly did not even consider, might such protests actually accomplish?

Well, it turns out that this isn’t the first time in our City’s history that the LA Times editorial board has not or would not understand that protesters might know what they’re doing better than the LA Times does. There are dozens of examples to choose from, involving civil rights, labor issues, and on and on and on. Among which this editorial, from October 5, 1965, on campus protests against the war in Vietnam,1 is worth quoting:

There is both room—and need—in this country for reasoned debate about the efficacy of U.S. policy, and such debate is being heard: in the news and opinion columns of newspapers, on the floor of Congress, and elsewhere. Criticisms being raised in these debates merit consideration, because any policy unable to withstand cogent scrutiny isn’t worth pursuing.

Thoughtful criticism, however, is seldom in evidence at the campus protest rallies. Sensible men know that in a democratic society there are better, more effective ways to make dissent known than through emotional, intemperate forums. For the fact of the matter is that the protest rallies on Vietnam aren’t going to change U.S. policy one whit.

According to the LA Times, then, these protests were futile, were not “going to change U.S. policy one whit.” And according to the LA Times, the proper response to the war was talk and more talk, not to mention “reasoned debate” in congress and in newspapers, even as thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, ultimately millions, of people were dying in Vietnam.

In 1964 and 1965 the protests the LA Times opposed attracted first dozens of people and then hundreds of people. In June 1967 more than ten thousand people rallied against the war at the Century Plaza hotel and in January 1968 more than a hundred thousand people protested at the Lincoln Memorial.

By March 1968 Lyndon Johnson announced that he wouldn’t seek reelection and by 1973 U.S. involvement in the war was over. So much for not “chang[ing] U.S. policy one whit.” So much for the theory that the best way to effect change is to sit around engaging in reasoned debate with killers like Lyndon Johnson and Eric Garcetti.

And it’s worth thinking about how this process works. If they’re not speaking to politicians, then who are protesters speaking to when they interrupt speeches, when they shut down schools and streets, when they’re rude, loud, uncivil? Well, it’s pretty clear from the way protest movements grow that one audience is other people.

People who are uncomfortable with a situation but haven’t found a way to articulate their discontent, people who don’t realize that they’re not the only ones who see the injustice, who see the pain and the damage caused by their rulers in their names, people who are yearning to take some action but don’t yet know what it might be or who they might act in concert with.

People who can make protests grow from ten to a hundred to a thousand to a million, who have the power to force a president out of office, to end a war. Who have the power to stop the LAPD from killing more children of color on our streets, from killing more homeless people because it’s in the bloody interest of the elites they serve.

It’s not necessarily politicians that we’re speaking to when we speak truth to power. The power of politicians is ultimately weaker than the power of the people to oppose them, to remove them from office, to stop them before they kill again. These are the powerful people we’re speaking truth to when we speak truth to power.

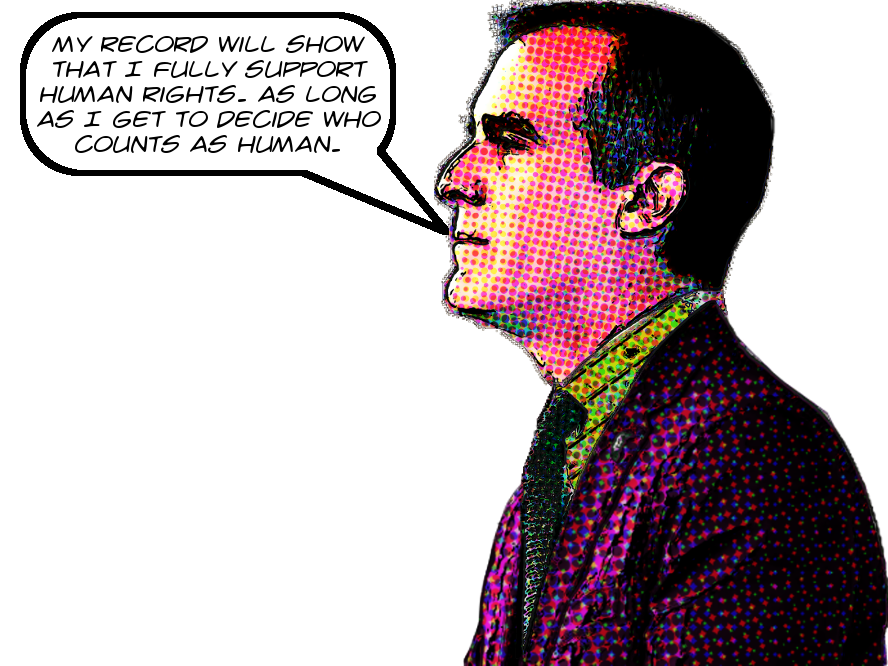

Image of Eric Garcetti is ©2018 MichaelKohlhaas.Org. Has some familial relation with this Eric Garcetti over here on the Twitz.

Dear Mike, I just recently joined DSA LA. Ever since the scales are falling from my eyes. I’m embarrassed, but not shamed. Choosing where to spend my 76 year old energy it’s a bit daunting. But, I’m working on it. Keep up the good work. I’ll be paying attention and reading your blog.

Thanks for the kind words, Terry! We’re glad to have you around.