It’s been a while since I wrote about the lawsuit that I was forced to file in August 2018 by the unhinged intransigence of the Fashion District BID, pursued by them in line with the unhinged intransigence of their soon-to-be-disbarred attorney, the world’s angriest CPRA lawyer, Ms. Carol Ann Humiston, in order to enforce my rights to read their damn emails. But time rolls on and the trial, scheduled for June 26, 2019 at 9:30 a.m. in Department 86 of the Stanley Mosk Courthouse, is rapidly approaching.

It’s been a while since I wrote about the lawsuit that I was forced to file in August 2018 by the unhinged intransigence of the Fashion District BID, pursued by them in line with the unhinged intransigence of their soon-to-be-disbarred attorney, the world’s angriest CPRA lawyer, Ms. Carol Ann Humiston, in order to enforce my rights to read their damn emails. But time rolls on and the trial, scheduled for June 26, 2019 at 9:30 a.m. in Department 86 of the Stanley Mosk Courthouse, is rapidly approaching.

Thus did my attorneys, Abenicio Cisneros and Karl Olson, file the trial brief with the court on Friday. The arguments are overwhelmingly powerful, and you can read substantial excerpts after the break. If I were the Fashion District after reading this I’d be ready to settle up and settle up quick. But they’re clearly on some kind of a mission with an axe to grind and a point to prove and I certainly don’t expect them to start acting sensible at this point. After all, it’s not their own money they’re squandering on Ms. Humiston’s exorbitant fees.1

As I said, you can read the specifics in the excerpts below, but there are two main general issues at stake. First is the fact that the BID relies heavily on the so-called catch-all exemption to the CPRA, found at section 6255(a), which allows agencies to withhold records when they can show “that on the facts of the particular case the public interest served by not disclosing the record clearly outweighs the public interest served by disclosure of the record.” The key thing here is that they have to make a showing of public interest in withholding the record.

This is hard enough to do in general, and the BID hasn’t even made an attempt, but our argument is that in the City of Los Angeles such a showing is even more difficult to pull off because (a) the BID is deeply involved in attempts to influence municipal legislation and (b) the Municipal Lobbying Ordinance at LAMC §48.01 establishes an extraordinarily high public interest in disclosure of information about attempts to influence:

The citizens of the City of Los Angeles have a right to know the identity of interests which attempt to influence decisions of City government, as well as the means employed by those interests.

…

Complete public disclosure of the full range of activities by and financing of lobbyists and those who employ their services is essential to the maintenance of citizen confidence in the integrity of local government.

The argument is essentially that the BID can’t even show that there’s any significant public interest in withholding the records they withheld, but given that the subject of these records concerns the means they employ to attempt to influence municipal decisions, they really especially can’t meet this extra-high local bar.

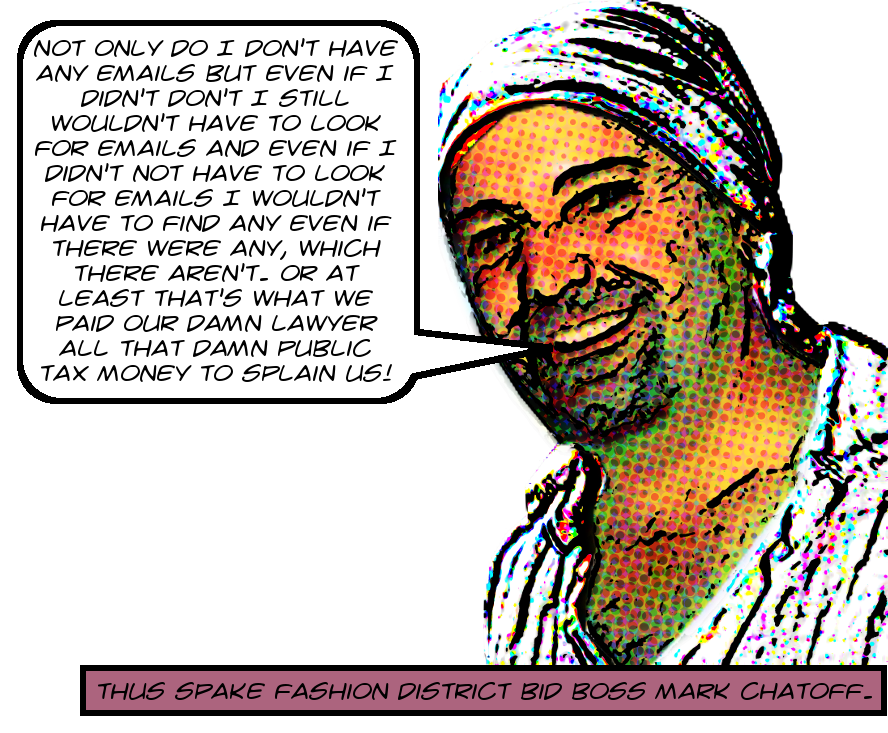

The other main argument is against some nonsense that the BID just made up in their reply to my petition. Many of the emails they refused to turn over are in the possession of their board members Linda Becker and Mark Chatoff. They wouldn’t even search for these because it’s Carol Humiston’s opinion that board members aren’t subject to the CPRA.

You can read the technical details below, but basically our argument is that the law that makes BIDs subject to the CPRA, which is Streets and Highways Code §36612, explicitly makes the owners’ associations subject. It makes no sense as a matter of law and as of a matter of common sense that a corporation could be subject to the CPRA while its board members were not subject. A corporation only does anything through the actions of the people who run it. And that’s the quick and dirty summary. As I keep saying, read on for the excerpts!

Transcribed selections from the opening brief:

I. INTRODUCTION

This is an action to enforce the California Public Record Act (“CPRA”) against the Downtown Los Angeles Property Owners Association, a.k.a. the Fashion District Business Improvement District (“the BID” or “Respondent”). Petitioner [Mike], a college professor, in 2017 requested easy-to-provide records related to the operation of the BID. Requested records include Board Member emails, BID communications with consultants retained to lobby the Los Angeles City Council regarding the BID’S renewal, and BID communications with the South Park BID and the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council. The BID, by a combination of delay, nonresponse, refusal to provide Board Members’ emails, and baseless assertion of the “deliberative process privilege,” has unlawfully frustrated public access to the requested records.

The BID has failed to meet the burden to justify non-disclosure which rests upon agencies resisting transparency under the Public Records Act. Accordingly, this Court should grant the Petition for Writ of Mandate and order the BID to disclose the records which it has withheld.

II. FACTUAL SUMMARY

A. Background on Respondent BID.

This litigation concerns three separate CPRA requests Petitioner [Mike] (hereafter “Petitioner”) submitted to Respondent, which contracts with the City of Los Angeles to manage the Fashion District Business Improvement District. 1 In 2018, the BID collected over $4 million in revenue, the large majority of which it obtains from assessments to parcels of real property which the City of Los Angeles collects and disburses to the BID. (Cisneros Deck 1J11.) The BID uses these funds to, among other things, operate a private 24-hour security force, to advocate to the City of Los Angeles on behalf of property owners, and to provide certain services such as graffiti cleanup. Respondent is subject to the CPRA under both its contract with the City of Los Angeles and pursuant to California Streets & Highways Code § 36612. Respondent’s Board of Directors is explicitly subject to the CPRA under its contract with the City of Los Angeles. According to a roster found on the BID’S website, as of 2016, Board Members listed non-BID email addresses as their official contacts.

B. Petitioner submitted three CPRA requests and the BID failed to comply with its

obligations under the CPRA.

At issue in this litigation are the BID’S responses to three CPRA requests which Petitioner submitted on May 17, 2017, July 7, 2017, and July 31, 2017, respectively. In replying to these requests. Respondent failed to comply with mandated response deadlines, denied access to records by refusing to conduct adequate searches, and unlawfully withheld records by improperly claiming the deliberative process privilege.

1. Request #1 – All Communications with the South Park BID and the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council and Chairman of the Board Mark Chatoff’s emails .

On May 17, 2017, Petitioner submitted a CPRA request (“Request #1”) to the BID. That request sought three categories of emails, two of which are at issue in this action. Item #1 sought all emails between anyone at the BID, staff or Board, and the South Park BID or the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council (“DLANC”) from January 1, 2016 through May 15, 2017. (Petition, U10.) Item #2 sought all emails from 2017 in the possession of Mark Chatoff, the Chairman of the BID’S Board of Directors, relating to the operation of the BID.

The BID did not respond within 10 days with a determination of disclosability and estimated date of production as required by Cal. Gov. Code § 6253(c). After nearly two months, and a July 6 reminder email from Petitioner, the BID substantively responded on July 14, providing a dropbox link 3 containing approximately 46 emails which the BID described as “the completed response.”

The July 14 response was deficient in several ways. The response did not include a determination as to whether each Item sought disclosable records in the possession of the BID and failed to inform Petition whether any records were being withheld subject to exemption. Most notably, the record production appeared incomplete: the production contained no emails from Board Members in response to Item # 1, and the disclosure did not contain even a single email from Chairman of the Board Chatoff in response to Item #2.

Rather than proceed directly to litigation, Petitioner made several attempts to learn whether responsive records were withheld and why the BID failed to produce any Chatoff emails. The BID provided no clarifications beyond asserting that “all non-exempt records have been submitted,” that “any exemptions are due to deliberative process,” and that “the BID has no records responsive” to Item #2. The BID declined to confirm whether responsive records were, in fact, withheld subject to a claim of the deliberative process privilege, or whether it asked Chatoff, or any other Board Member, to search for responsive emails. Petitioner brought the request to Chatoff’s attention directly in an August 18,2017, email, but neither BID staff, nor Chatoff, produced additional records.

Petitioner has obtained-via CPRA requests to other BIDs-records responsive to Items #1 and #2 which were not produced. Those records include emails from BID staff to individuals at the South Park BID and DLANC responsive to Item #1 which were not included in the dropbox production. The BID either unlawfully withheld these records under the deliberative process privilege, or failed to conduct an adequate search to locate them.

2. Request #2 – Emails between the BID and Urban Place Consulting (“UPC”)

On July 7,2017, Petitioner submitted a CPRA request (“Request #2”) for “all emails between anyone at UPC and anyone at the BID (staff and Board) exclusive of [BID Executive Director Rena Leddy] from January 1,2017 through whenever you comply with this request.” (Petition HI 7.) UPC, a consulting firm that specializes in serving BIDs, contracted with Respondent in January 2017 to provide services related to the BID’S upcoming renewal. The scope of UPC’s services under the contract includes attending/facilitating Steering Committee Meetings, creating a multi-year Management Plan and Engineers Report, refining BID budget for inclusion in the management plan, and testifying at Council committee meetings and Council meetings as necessary.

The BID responded on July 17, asserting that Request #2 sought “some records which are exempt from disclosure as deliberative process” and estimating that it would provide all non-exempt records and information “within the next two weeks.” Petitioner challenged the BID’s assertion of the deliberative process privilege, citing to the public interest in municipal lobbying as stated by the Los Angeles Municipal Lobbying Ordinance (Los Angeles Municipal Code § 48.01, et seq.) In response, BID Director Leddy reasserted “I have determined again that the exemption raised applied.”

The BID did not provide records within two weeks. (Petition f21.) Petitioner inquired as to the request on August 18th, but received no response until October 13th. In that response, the BID stated, confusingly, both that Request #2 sought records exempt under the deliberative process and that the BID did not have responsive records.

The BID’s claim that no records exist is not credible. The UPC contract indicates that UPC was attending and facilitating meetings with the BID’s Renewal Steering Committee. Those meetings took place twice monthly in 2017 and included Board Members. As such, it is very likely that BID Board Members possess email communications regarding those meetings. Further, given the wide scope of UPC’s services, it is likely that UPC corresponded with BID staff members such as the Finance Manager, Operations Director, or Marketing Coordinator. Therefore, it is likely the BID simply refused to search for staff and Board Member emails and/or unlawfully withheld all responsive staff emails under a claim of deliberative process privilege.

3. Request #3 – Board Member Linda Becker’s emails.

On July 31,2017, Petitioner submitted a request (“Request 3”) for copies of all 2017 emails in the possession of Linda Becker. Becker is a BID Board Member and was chair of the BID’s Renewal Steering Committee. The BID did not respond within 10 days with a determination of disclosability and estimated date of production as required by § 6253(c). On August 18, Petitioner inquired as to the status of the request. The BID responded that there were no responsive records and that it was not claiming exemptions.

Petitioner informed the BID that either a responsive record must exist, or it was deleted after the BID received the request, because the BID emailed Board Members in early August regarding an upcoming meeting. Thus, either Becker failed to produce that email, or the BID never asked Becker to search for records, or Becker deleted the records in response to the request.

The BID, evidently upon realizing that Petitioner was correct, changed its tune. The BID now asserted that Request #3 sought records “exempt from disclosure pursuant to the deliberative process privilege” and the BID agreed to provide the email advising Becker of the Board Meeting. The BID did not agree to ask Becker to conduct a search for records.

Despite Petitioner’s additional attempts to obtain records, the BID has, to date, failed to produce even a single email from Becker in response to this request, including the email advising Becker of the Board Meeting.

III. LEGAL ARGUMENT

The BID has violated both the procedural and substantive requirements of the CPRA such that declaratory relief and a writ of mandate are necessary. The BID repeatedly failed to comply with procedural requirements. The BID unlawfully denied access to and withheld records by failing to conduct adequate searches for BID staff records, by improperly invoking the deliberative process privilege, and by categorically refusing to search for BID records held in BID Board Members’ email accounts. This Court should declare that the BID must comply with the CPRA’s procedural requirements, declare that Board Member emails are subject to the CPRA and must be produced, and issue a writ of mandate directing the BID to conduct a reasonable search for records and to provide all responsive non-exempt records.

A. The BID repeatedly violated procedural requirement of the CPRA such that declaratory relief is warranted.

The BID’s disregard for the CPRA’s procedural requirements warrants declaratory relief. Requestors are permitted to sue for declaratory relief under the CPRA. § 6258. Declaratory relief is appropriate where an “actual controversy” exists. An “actual controversy” includes a probable future controversy, so long as the controversy is ripe. Whether a future controversy is probable can turn on whether evidence shows that a Respondent will continue the offending practice. A court can presume a Respondent will continue an offending practice in light of a Respondent’s refusal to admit the violation.

The BID repeatedly failed to comply with the provisions of § 6253(c). Upon receiving a CPRA request, an agency is required to respond within 10 days with a determination as to whether the request, in whole or in part, seeks copies of disclosable public records in the possession of the agency along with an estimated date of production. § 6253(c). Here, the BID failed to respond within 10 days whatsoever with respect to Requests #1 and #3. (Petition 11,24.), While the BID responded within 10 days to Request #2, it did not provide a determination as to whether the request sought disclosable records in the BID’S possession. Rather, it merely opined that “some” of the requested records were exempt.

In all cases, the BID failed to provide a determination within 10 days as to whether Petitioner could expect the BID to provide records in response to his requests. Similar to the agency in California Alliance, the BID refused to admit the violation (“Respondent denies an untimely or improper response. giving rise to the presumption that the violation will reoccur.

The BID also failed to inform Petitioner whether it actually withheld records in response to his requests. Where an agency withholds responsive records on the basis of a statutory exemption, “the agency … must disclose that fact.”

Here, in response to all three requests, the BID invoked the deliberative process privilege but did not confirm whether responsive records were actually withheld under that exemption. Again, in its Answer, the BID denied that its responses were improper.

Thus, the BID repeatedly failed to comply with the procedural requirements in § 6253(c) and § 6255. The BID’S refusal to admit its violations indicates that it will violate those provisions moving forward. Declaratory relief is warranted and should issue.

B. The BID unlawfully withheld records in response to all three requests.

The BID unlawfully denied access and withheld records in violation of the CPRA.

1. General Principles of the CPRA

Pursuant to the CPRA, individuals have a right to access public records. § 6250, et seq. In statutorily defined “unusual circumstances” an agency can claim a 14-day extension to provide its § 6253(c) response. The BID did not claim that extension here.

In enacting the CPRA, the Legislature declared that “access to information concerning the conduct of the people’s business is a fundamental and necessary right of every person in this state.” § 6250; To facilitate the public’s access to this information, the CPRA mandates, in part, that an agency, upon a request for records that reasonably describes an identifiable record or records, shall make the records promptly available. § 6253(b).

While the CPRA provides permissive exemptions to its disclosure requirements, these exemptions must be narrowly construed and the agency bears the burden of showing that a specific exemption applies. Even if portions of a document are exempt from disclosure, the agency must disclose the remainder of the document. § 6253(a).

The CPRA requires that an agency “assist the member of the public [to] make a focused and effective request that reasonably describes an identifiable record or records” by taking steps to ”[a]ssist the member of the public to identify records and information that are responsive to the request or the purpose of the request, if stated” and must “[p]rovide suggestions for overcoming any practical basis for denying access.” § 6253.1.

If an agency fails to comply with these provisions, the CPRA authorizes a requestor to file a petition for writ of mandate to enforce the right to inspect or to receive a copy of records. § 6258. If the Court finds that the failure to disclose is not justified, it shall order the agency to make the record public. § 6259(b).

Public policy favors judicial enforcement of the CPRA. The CPRA contains a mandatory attorney’s fee provision for the prevailing plaintiff. § 6259(d). The purpose of the provision is to provide “ protections and incentives for members of the public to seek judicial enforcement of their right to inspect public records subject to disclosure.” A plaintiff prevails under the CPRA where the plaintiff shows that an agency unlawfully denied access to records. An agency is not protected from liability merely because the denial of access was due to the agency’s internal logistical problems or general neglect of its duties.

2. BID Board Member emails related to BID business are subject to the CPRA, regardless of where they are held.

All three requests at issue call for emails in the possession of BID Board Members. These emails are subject to the CPRA under both City of San Jose v. Superior Court (2017) .Cal.5th 608 (City of San Jose ) and the BID’s contract with the City, regardless of whether the emails are located in a BID-controlled email account or device, or in a private email account or device.

BID Board Member emails are subject to the CPRA under the California Supreme Court’s decision in City of San Jose. There, the Requestor sought emails from the mayor, two city council members, and their staffs, regardless of whether those emails were located in public or private devices and accounts. The Court held that emails relating to public business in private devices and accounts of public officials and employees are within the scope of the CPRA. The Court’s reasoning, as applied to this matter, shows that BID Board Member emails are similarly within the scope of the CPRA, regardless of where those records are held.

Emails can be “public records” under § 6252(e), even if located in private accounts. In City of San Jose, the City argued that employee emails in personal accounts were not “prepared, owned, used, or retained” by the agency and thus not “public records” under § 6252(e). Id. at 619. The Supreme Court rejected this argument by invoking the “prepared by” prong of § 6252(e).

The Court also rejected the City’s contention that emails in private accounts were not “public records” because the individual officers and employees are not a “local agency” under § 6252 and thus records “prepared by” these individuals were not prepared by the agency. Id. at 620. The Court found this argument flawed. Id. The City’s narrow construction of a statute conferring access to records violated the constitutional directive of broad interpretation of the CPRA to further access. Id. Further, the term “local agency” logically includes the individual officers and staff who conduct the agency’s affairs because:

It is well established that a governmental entity, like a corporation, can act only through its individual officers and employees. A disembodied governmental agency cannot prepare, own, use, or retain any record. Only the. human beings who serve in agencies can do

these things.

Thus, the Supreme Court found that individual public officials and employees can “prepare” records subject to the CPRA and, thus, their emails are not categorically exempt under § 6252.

The Court also found that an agency has a duty to search for emails held in private accounts under § 6253(c). The City argued that emails in the personal accounts of employees and officers were beyond the City’s reach and, thus, fall outside the CPRA. Id. at 622. The Supreme Court rejected this argument. First, the Court found that, in addition to having been “prepared by” the agency, a writing retained by a public employee conducting agency business has been “retained by” the local agency within the meaning of § 6252(e), “even if the writing is retained in the employee’s personal account.” The Court continued that a record “in the possession” of individual officers and employees is, in fact, “in the possession of’ an agency under § 6253(c). The Court explicitly rejected the City’s contention that a document concerning official business is only a public record if it is located on a government agency’s computer servers or in its offices, stating:

Likewise, there is no indication the Legislature meant to allow public officials to shield communication about official business simply by directing them through personal accounts. Such an expedient would gut the public’s presumptive right of access and the constitutional imperative to broadly construe this right. Thus, an agency must search for public records held in private email accounts under § 6253(d).

The Court also identified policy considerations underlying its decision. The Court emphasized that the CPRA’s purpose-to ensure transparency in government activities-would be undermined if the CPRA could be evaded simply by use of a private account. Id. at 625. The Court rejected that public official and employee privacy is necessarily invaded by its holding, stating that “any personal information not related to the conduct of the public business could be redacted, and that the Act itself provides exemptions to accommodate this concern.” Finally, the Court explicitly rejected the City’s argument that a search for documents, in and of itself, is an evasion of privacy sufficient to exclude privately held emails from the CPRA. Thus, City of San Jose is a powerful statement in favor of the disclosability of public records, regardless of whether they are held in a private or agency-controlled accounts and devices.

Emails held in BID Board Member’s private email accounts and devices are subject to the CPRA under City of San Jose. The analysis in City of San Jose did not turn on whether public officials were paid or unpaid, or whether an agency had “constructive control” of records held by employees. Rather, as discussed above, it turned on whether public officials and employees were the embodiment of the agency. Because the Court found they were, it found that the term “local agency” encompassed public officials and employees, that records prepared by officials and employees are prepared by the agency, and that records possessed by officials and employees are possessed by the agency. The same analysis applies to BID Board Members, irrespective of whether BID Board Members are employees or non-employees, paid or volunteer.

In fact, the reasoning in City of San Jose applies even more strongly to BID Board Members than to City employees. The City of San Jose Court held that the term “local agency” encompasses officials and employees by reasoning analogously to a corporation Id. at 621. Here, the BID ]s a non-profit corporation, and no analogy is required. As a corporation, the BIDs activities and affairs are conducted by the Board and, by law, all corporate power is exercised by or under the direction of the Board. See Cal. Corporations Code § 5210; There is no question that, as a corporation, the BID’S Board of Directors are the embodiment of the BID when conducting BID business. Thus, to the extent that public records held in the private accounts of public officials and employees are subject to the CPRA, so, too, are those records held in the private accounts of BID Board Members.

The policy considerations in City of San Jose also dictate that Board emails are subject to the CPRA. Just as the public’s right of access would be “gutted” if public officials could evade the CPRA by simply using private accounts, so, too, would that right be gutted if BIDs could evade transparency by conducting business in private accounts. The Legislature explicitly made BIDs subject to the CPRA. Its judgment would be undermined if the BIDs could so easily sidestep the CPRA’s requirements. Further, just as the privacy concerns in City of San Jose were not sufficient to “tip the scales” in favor of categorical non-disclosure, so too, does any privacy concern fail to tip the scales here. As such, emails related to BID business, created or held by BID Board Members, are subject to the CPRA under City of San Jose, regardless of where those records are held.

Board Member emails are subject to the CPRA under the BID’S contract with the City of Los Angeles, even assuming, arguendo, they are not subject under City of San Jose. That contract explicitly states that the “Corporation and the Board of Directors are also subject to and must comply with the California Public Records Act.” (emphasis added) (Petition ^ 13.). The contract, entered into prior to the Court’s decision in City of San Jose, removes any ambiguity that the Board of Directors-as distinct from the Corporation-is subject to the CPRA, and it provides no limitation based on whether Board Members hold records in private or BID-controlled accounts and devices. As such. Board Member emails are subject to the CPRA under the BID’S contract with the City.

In conclusion, under both City of San Jose, and the BID’S contract with the City of Los Angeles, BID Board Member’s emails related to the operation of the BID are subject to the CPRA, regardless of whether they are held in private accounts. Thus, Petitioner’s requests triggered the BID’S duty to search for and provide BID Board Member emails, which it failed to do. Declaratory relief and a writ of mandate should issue.

3. The BID denied access and unlawfully withheld records in response to all three of Petitioner’s requests .

The BID, in response to all three of Petitioner’s CPRA requests, violated the CPRA by unlawfully denying access to and/or withholding records.

As an initial matter, all three of Petitioner’s requests called for emails sent or received by BID Board Members. The BID failed to provide even a single BID Board Member email, presumably based on its belief that Board Member emails held in private accounts fall outside of the reach of the CPRA. As shown above, that position is incorrect. The BID had a duty to search for those records and, in refusing to do so, violated the CPRA and unlawfully denied Petitioner access to those records.

It is possible that, in the time since Petitioner made his requests or filed this litigation, BID Board Members destroyed all responsive emails in their possession. The BID may argue that, because those emails have been destroyed, Plaintiff cannot “prevail” in this litigation or be entitled to an award of costs and attorney’s fees under § 6259(d). The BID’S reliance on a subsequent destruction of records would be misplaced. … Thus, if this Court finds that BID Board Member emails located in non-BID accounts are subject to the CPRA, Petitioner has prevailed, even if Respondent subsequently destroyed all responsive records.

The BID also unlawfully denied access to staff emails-either by a failure to search or by overclaiming exemptions-in response to Requests #1 and #2. Regarding Request #l-staff and Board emails to the South Park BID and/or the DLANC- Petitioner has obtained multiple emails which are both responsive to this request, and do not fall under any exemption. ( The BID failed to provide these emails in response to Petitioner’s request. While the BID has declined to state whether it actually withheld responsive records, it is clear from the responsive, non-exempt emails Plaintiff obtained from other BIDs, that the BID unlawfully denied access to staff emails, either via an inadequate search or by overclaiming the deliberative process privilege.

Regarding Request #2-staff and Board emails (exclusive of Director Leddy) to UPC-the BID failed to provide even a single record in response to this request. As with Request #1, the BID did not clearly state that it withheld records subject to the deliberative process. However, given the total lack of a production, and the extremely high likelihood that UPC communicated with BID staff and Board Members-in light of the twice monthly Renewal Committee meetings and the wide scope of UPC’s duties under its contract for services-it is clear the BID unlawfully denied access, either via an inadequate search or by overclaiming the deliberative process privilege.

4. The public interest in disclosure of these records is significant.

There is a significant public interest in all requested records. As stated above, the Legislature determined BID operations should be transparent, establishing the public interest in disclosure of even mundane records related to the BID. Here, the political nature of these records amplifies the public interest in disclosure.

BIDs use publicly-disbursed monies to collaborate to wield political influence on issues such as homelessness Respondent, during this period, coordinated with other BIDs to impact the Skid Row Neighborhood Council formation election. Los Angeles BIDs, including Respondent, participate in the Los Angeles BID Consortium, an association through which BIDs share information and coordinate political advocacy.

Withheld records responsive to Request #1 include records related to the BID Consortium and other inter-BID political collaboration on issues such as homelessness, street vending, and the Skid Row Neighborhood Council Formation Election. Given the political nature of those emails, the public interest in disclosure is high.

Request #2 pertains directly to the BID’S lobbying of the City Council related to Council’s renewal of the BID via ordinance. The high public interest in City lobbying is illustrated by the Los Angeles Municipal Lobbying Ordinance, Los Angeles Municipal Code § 48.01, et seq. As these records concern how the BID engages consultants to lobby on its behalf, the public interest in disclosure of these records is high.

C. The Court should inspect withheld records in camera prior to finding they were properly withheld.

To the extent the BID actually withheld records subject to exemptions. Petitioner requests that the Court examine the records in camera before finding they were properly withheld. 7 An in camera examination is explicitly permitted and contemplated by the CPRA. § 6259(a).

The only exemption the BID invoked is the so-called deliberative process privilege. This is not an absolute privilege, but rather it applies only when a public agency can meet the burden of showing that the interest in non-disclosure of a record “clearly outweighs” the interest in disclosure under § 6255. “Not every disclosure which hampers the deliberative process implicates the deliberative process privilege. Only if the public interest in nondisclosure clearly outweighs the public interest in disclosure does the deliberative process privilege spring into existence.” Respondent has made no showing of any strong interest in non-disclosure and has not established that any of the communications it has withheld are either “pre-decisional” or “deliberative.” Here … Respondent has not met, and cannot meet, its burden of establishing any deliberative process privilege because public interest in disclosure is high, and there is no cognizable interest in non-disclosure which would “clearly outweigh” that interest. Because the deliberative process privilege is subject to balancing, and because an agency must show clear overbalance on the side of nondisclosure to claim the privilege, the deliberative process privilege is a “limited, qualified public disclosure exemption.”

It is insufficient for an agency to merely invoke the policy underlying the deliberative process privilege to withhold records; an agency must make a specific factual showing as to why the privilege is necessary to protect the deliberative process in that instance.

When an agency fails to meet its burden of justifying non-disclosure, a court can and should order disclosure of records without conducting an in camera review. The Court can also conduct an in camera review under Government Code section 6259(a) if it concludes that the matter cannot otherwise be resolved. Accordingly, the records sought should be ordered disclosed or, in the alternative, the court should conduct an in camera review and then, after review, order disclosure.

IV. CONCLUSION

The public’s right to know, expressed in statute. Constitution, case law, and voter initiative, is well established in California. Here, the BID has shirked its responsibilities under the CPRA by failing to comply with procedural requirements, by failing to conduct an adequate search of staff emails, by unlawfully withholding records, and by categorically refusing to provide BID Board Member emails. This Petition should be granted and the BID should be ordered to disclose the records sought by the Petition.

Dated: April 25, 2019 By:

Abenicio Cisneros.

Attorney for Petitioner and Plaintiff

Image of Fashion District BID Boss Boy Mark Freaking Chatoff is ©2019 MichaelKohlhaas.Org and don’t forget to gaze upon this Markie Boy over here.

- During litigation the amounts of payments to attorneys aren’t disclosable under the CPRA because of attorney/client privilege, but when the litigation is over they become disclosable. So pretty soon we’ll find out how much the BID is paying this lawyer. Or at least how much their insurance agency is paying her, which is what seems to happen in a lot of these cases.